by Manlio Masucci, Navdanya International

“It’s time for action”, says Vandana Shiva, who has gathered experts from all over the world to draft a Manifesto that will provide farmers, consumers, activists and civil society organizations with the basic tools to claim their right to healthy food. The publication’s title “Food for Health“, has become the key title for an international campaign, which brings together environmental movements and scientists from all over the world in order to spur the needed paradigm shift for the well-being of the planet and all its living beings.

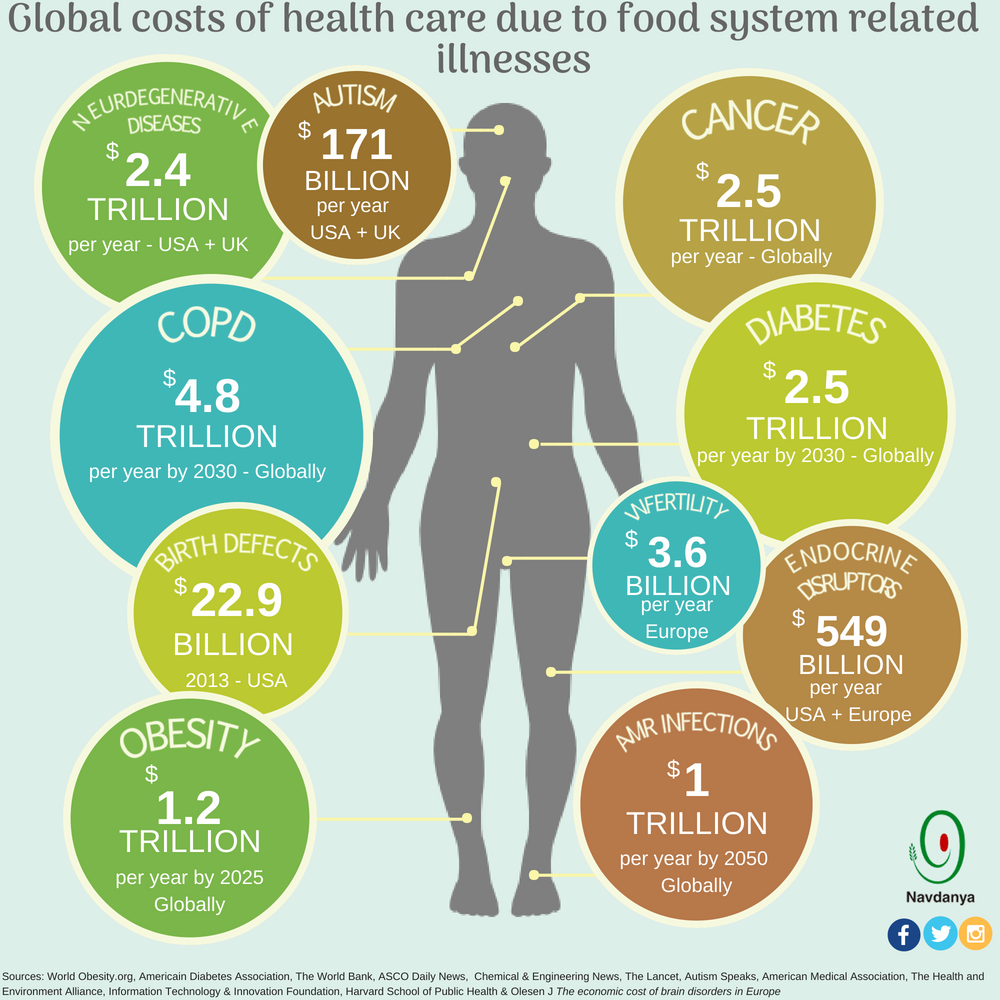

The need for an informative campaign and an action plan at a global level on the harmful effects of industrial food production on the environment and on our health, is made clear by years of studies, analyses and comparisons which leave no room for further doubt. The current productive model, based on industrial agriculture with high chemical input and large-scale distribution, has failed in terms of its social, cultural and labor objectives. It contributes, in a decisive way, to soil and groundwater pollution by releasing a significant amount of pollutants into the environment, and thus also contributing to climate change and biodiversity loss. Food commodities that are put on the market also have low nutritional value, as well as being potentially toxic. The consumption of industrial food increases the risk of disease which, in turn, has a huge impact on the budgets of public health systems worldwide.

The tragic irony is that it is the taxpayers themselves who are bearing the real costs of this productive model, which greatly relies on public funding in order to keep functioning. Indeed, both the money needed to pay subsidies to agribusiness companies, the costs of environmental damage and public health, are taken from the pockets of taxpayers who, in the meantime, are under the illusion that if they keep buying cheap food in supermarkets they are saving money on the food they consume regularly.

“The health of the planet and the health of the people are one,” Vandana Shiva reminds us. It’s time to overcome the reductionist and mechanistic paradigms at the basis of our agriculture and food production models, and reclaim the essential connections necessary for our survival and well-being. The connection between food and health precisely represents one of those broken connections that must be rebuilt. The authors of the Manifesto have presented scientific evidence from their respective fields of expertise and coming to a common conclusion: the production and consumption of industrial food is linked to a wide range of diseases and nutritional deficiencies. This applies, in particular, to those commonly defined as “non-communicable diseases” (NCD), which today cause no less than 70% of deaths worldwide, a total of 40 million deaths per year, out of which 15 million are people under 70. Despite the fact that health emergencies, cancer pandemics, and degenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s are often interpreted as unfortunate but chance cases, these diseases are clearly associated with people’s eating habits. Is ignoring the influence of environmental factors on our health simply a distraction? Not really, considering the economic interests behind the system of industrial food production.

The aim of the Manifesto is therefore to analyse and connect the state of our planet’s health with that of people, by identifying the main risk factors that require necessary corrective action, along with building the awareness that we are facing epochal systemic challenges.

Indeed, the risks to people’s health are to be looked at in the context of the current industrial economic system, which puts private interests at the centre, and the common good second. This extractivist system bypasses democratic values and aims to maximise profits by outsourcing the real costs to citizens. Thus, the reconstruction of a disintegrated knowledge system, through reconnecting traditional knowledge with new technologies, is the starting point of the Manifesto, which poses potential and immediately feasible alternatives. The defence of biodiversity, the support of local economies and rural production at 0 km, the recovery of traditional cultures and knowledge, the revival of agroecology and the ethical use of new technologies are some of the proposed solutions contained in the Manifesto.

The evidence revealed by these data requires that anyone who is concerned about the present and future of our planet along with its inhabitants, must mobilise and demand that governments undertake radical changes in the current economic, productive and distribution systems. The “Food for Health” Manifesto is meant to serve as a reference tool to relaunch and reclaim the rights of the planet, and all its life-forms, to transform the food production systems that are responsible for the current environmental and health degradation, into healthy systems capable of generating well-being. As Vincenzo Migaleddu, former president of ISDE Sardinia (International Society of Doctors for the Environment), affirmed: “the right to health is the right to a healthy life, not the right to be cured.”

A broken economic system

There is something profoundly wrong when an economic system, based on the mantra of increasing production at all costs, not only fails to achieve its promised result, but also produces side effects of unprecedented severity, the costs of which are externalized to governments and its taxpayers. The Green Revolution was supposed to solve the global food problem through industrialization of the agricultural sector, but this has only been a broken promise. Now, these are not just the words of civil society organizations, but also of the FAO itself, who just a few years ago acted as one of the main proponents of the Green Revolution.

The evidence is now clear for all to see, including the FAO’s Director General, Graziano da Silva, who closed the recent Symposium on Agroecology held in Rome, by stating that, “We have reached the limit of the paradigm of the Green Revolution,” and that, “We cannot continue to produce food in the same way we have, relying on intensive farm techniques, chemical inputs and mechanization, and we need to shift to a more holistic approach on sustainability.” According to the FAO’s Director General, the Green Revolution has not been able to solve the issue of global hunger, as in 2016, 815 million people are still suffering from hunger globally. This figure is accompanied by two other important points: in the same year, almost two billion people were overweight, while 650 million were obese. The mantra of productivity at all costs, stressed again Graziano Da Silva, has come with an unsustainable cost from an environmental point of view, because of the massive use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides that have contributed to soil contamination, pollution of aquifers, and loss of biodiversity.

It is then clear that this issue goes beyond production data, considering that most of the food we eat is still produced by small and medium-sized farms, while the vast majority of industrial crops, such as maize and soy, are mainly used as animal feed or to produce biofuels.

Economic globalization and industrialization have, therefore, not solved the issue of world hunger, but have rather increased waste. As confirmed by the FAO, about a quarter of the food produced, 1.3 billion tons, is lost along production chains.

The relentless increase in production, much to the detriment of the environment and food quality, has not only failed to solve the existing problems, it has also created new ones. It is clear that the real issue revolves around distribution and access to food, as Nadia El Hage, researcher at FAO and one of the authors of the Manifesto, points out. “The real problem,” explains El Hage, “is that people do not have access to the resources they need to buy or produce food: in Asia, for example, there is enough food for the entire population – and Asian countries are even exporting food – yet there are still many people who face hunger. We must recognize that there is a problem of justice in the food system.”

The “Food for Health” Manifesto pushes it further, by directly challenging the agribusiness multinationals engaged in taking over more and more arable land. Their goal is to increase production and extend their control over the agricultural sector through the acquisition of seed patents, monopoly on crops and price control. An extractive model where food is no longer human heritage, but instead a commodity or tool aimed at creating monopolies which does not take into account the nutritional, cultural and social value of food. The recent investigations, known as the “Monsanto Papers” and the “Poison Papers” have brought to light the strategies implemented by the major agrochemical groups to expand their empire: from lobbying actions, to interference in governmental agencies’ proceedings, to mega mergers and acquisitions, and – in collusion with institutions – attacks directed against independent science.

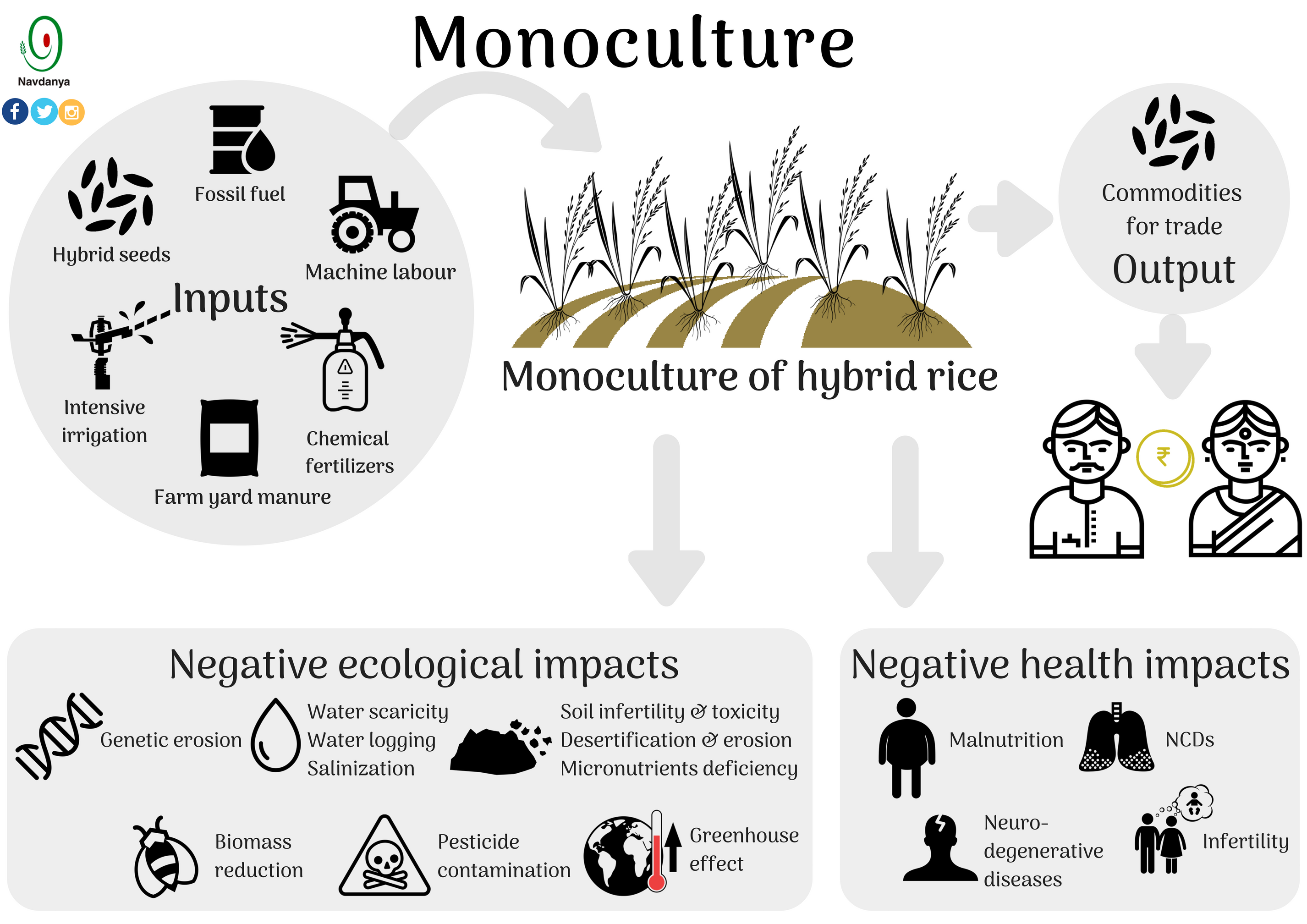

This could not be any other way, considering the evident unsustainability of the industrial agricultural model, which can no longer hide its real costs to the environment and society. Industrial agricultural production requires high energy inputs and contributes significantly to climate change by accounting for 29% of all greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere. Intensive, highly polluting factory farming, which covers 70% of agricultural land and 30% of the total surface area of the planet, is also included in the calculation. The use of fertilizers and pesticides is also causing extremely costly side effects. The use of chemicals is depriving the soil of its natural nutrients, while at least 210 new species of super weeds have developed resistance to herbicides.

What, then, are the real costs of this global productive system- the costs which we don’t see on our receipt when we check-out at the supermarket? The group of experts who drafted the Manifesto have compared some of the most significant data from all over the world and have come to the conclusion: even from an economic point of view, the current productive system – based on industrial agriculture – is not sustainable. For example, in the United States, one of the largest consumers of agrotoxic products in the world, the environmental and public health costs resulting from the use of pesticides in the 90s, amounted to 8.1 billion dollars a year, compared to an annual expenditure of 4 billion for the purchase of agricultural chemicals. In short, for every dollar spent to buy pesticides, an additional two dollars were spent to deal with the damage caused by their use. This estimate is similar to the results of a survey, published in Brazil in 2012, on cases of acute pesticide poisoning in the State of Paraná. The total health costs for the Brazilian State amounted to 149 million dollars each year, meaning an expense of 1.28 dollars for every dollar spent in the purchase of pesticides.

As far as Europe is concerned, the damage caused by pesticides has cost the public health system over 190 billion euros. But this is a conservative estimate, considering that only cognitive deficits, which are secondary effects of exposure to organophosphorus pesticides, are taken into account and that not all EU countries are aligned in their assessments. This is the case in France which, as early as 2012, recognised the link between Parkinson’s disease and exposure to pesticides. The link was confirmed by a recent study of the Canadian University of Guelph, that has classified the disease as an occupational disease affecting farmers.

That’s a partial but already salacious bill that multinationals lay directly at our doorstep, preferring, in the meantime, to calculate the millions in dividends they have accumulated by plundering the planet’s resources. We are talking about huge damages that would render the industrial production model unsustainable if the costs were not systematically externalized.

Clearly, when we buy in supermarkets, the high environmental and human health costs are not reflected in the listed price, fuelling the illusion that we are saving money. While in actuality, industrial agriculture is generating fortunes for manufacturing companies and its shareholders and certainly not for those of the planet and its inhabitants.

The industrial agricultural sector can be defined as one of the principal actors of “predatory globalization” which prefers to be based on the efficiency of capital, rather than on people’s well-being. First of all, this is a political issue, considering that industrial food is produced at high costs, because of public subsidies, and is marketed internationally through the so-called “free trade treaties”. Local markets, flooded with cheap junk food, lose their suppliers and farmers who, under the pressure of a contrived productive system, are forced to abandon their land.

This is the noose that each day tightens more and more around the necks of farmers who, confronted with the interests of big agribusiness, are no longer in a position to produce healthy food, thereby leaving consumers without the possibility of choosing their diet.

Damaging biodiversity means damaging ourselves

In order to understand how harmful the system of industrial agricultural production is to people’s health, it is essential to make reference to the concept that inspired the drafting of the Manifesto. The health of people and the health of the planet must be considered as one. Human beings cannot and must not think of themselves as separated entities, with respect to the planet they live. This ancient wisdom was already held by the Greeks, as demonstrated by the maxim of Hippocrates, the most famous physician in history, who invited his patients to consider food as the true and only medicine. A teaching that is also found in Ayurveda, the science (Veda) of life (Ayur), centered on food.

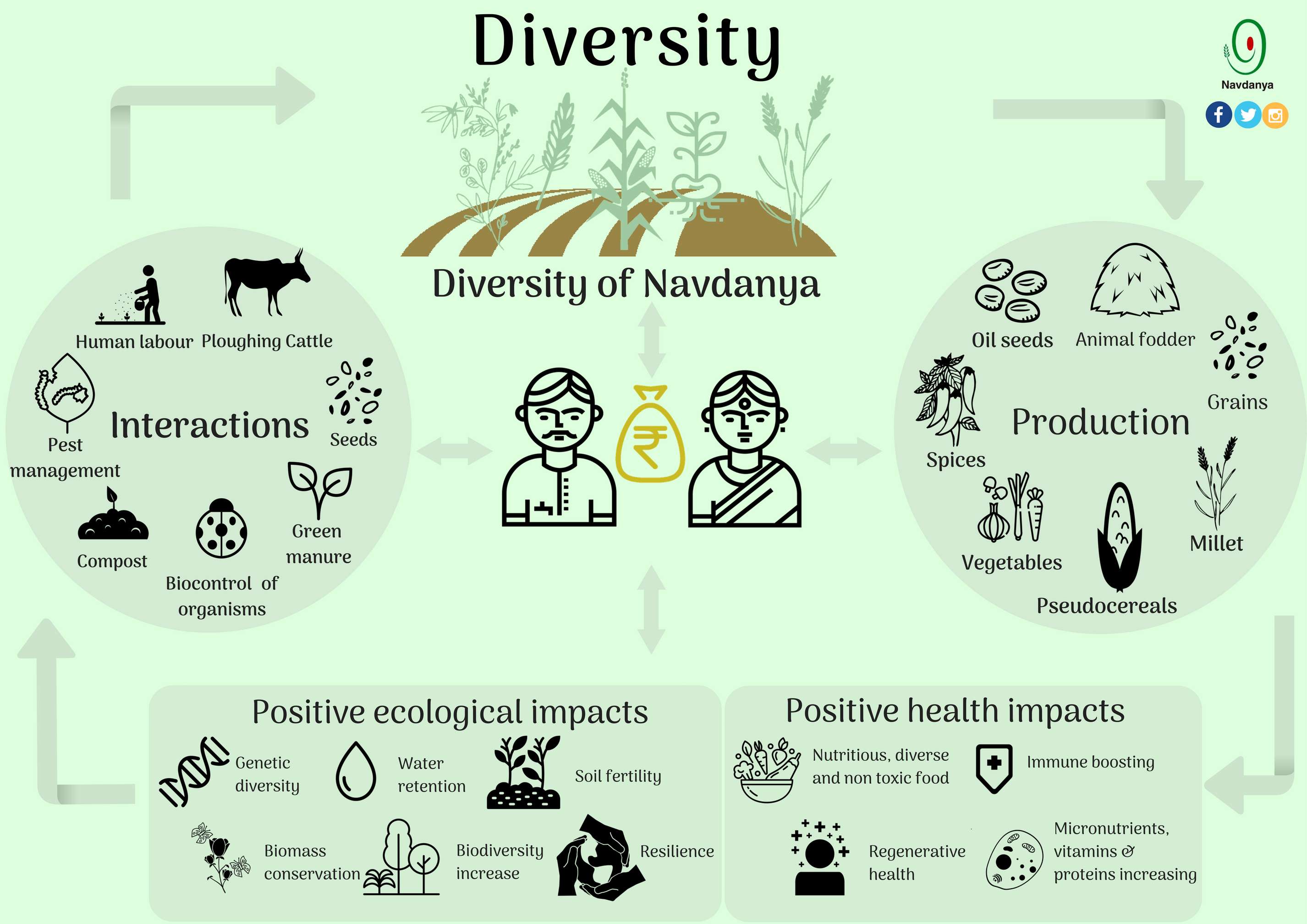

Indian farmers have practiced ecological agriculture for 10,000 years, based on soil care, biodiversity intensification and the “Law of Return“. These ancient practices were based on multiple scientific and ecological principles that upheld the laws of nature and social welfare.

This knowledge – acquired over thousands of years – has not, however, prevented the imposition of a productive model based on diametrically opposed principles. When it comes to exposing the damage that an industrial productive system based on intensive monocultures does to the planet’s biodiversity, it is necessary to understand to what extent human beings are part of that same biodiversity and how much they share the risks. It is no coincidence that more and more researchers are focusing on the relationship between the loss of biodiversity and the increase of inflammatory diseases. The decline in our immune system’s ability to properly function is associated with the state of health of our microbiome, which is the system of bacteria, viruses, fungi, yeasts and protozoa that are part of our intestines. Also called by scientists our “second brain”. It performs a number of important functions that significantly contribute to the health of our immune system. A poor functioning microbiome, or its lack of diversity, entails greater risks of developing various neuropsychiatric disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, autism, anxiety. In addition to this, recent research has confirmed that the composition and diversity of the microbiome is very important in determining anti-tumor immunity. The fact that the human microbiome is in distress is confirmed by a practice that is becoming rapidly widespread in medical circles: namely the transplantation of faeces, aimed at transferring a healthy microbiome into a patient whose microbiome is no longer functional.

So, the importance of the microbiome for human health is established, but how do we cultivate a healthy microbiome? The good news is that we are responsible for the good health of our microbiome, which is not genetically inherited, but rather affected by environmental factors in its formation. That is why researchers agree with the assertion that food diversity is of crucial importance for a healthy microbiome.

Alas, it is precisely at this stage that there is bad news. Modern “market-imposed” diets are in fact loaded with unhealthy ingredients such as sugars and fats, while diversity seems to be ruled out by a standardization process that, once again, works in the interests of the market rather than the health of the consumer. As Salvatore Ceccarelli, international expert in Agronomy and Plant Genetics, and one of the authors of the Manifesto, explains: “How can we have a diet based on diversity, if 60% of our calories come from just three plant species, ie wheat, rice and corn? And how can we have a diet based on diversity, if almost all the food we eat is produced from seed varieties that, in order to be legally traded, must be registered in a catalogue that is called register of varieties, and that, in order to be recorded in this register, must be uniform, stable and recognizable? Between the need to eat ‘diverse’ foods discussed so far, and the uniformity in food products required by laws on crops, there is a clear contradiction.”

Industrial agriculture not only limits the varieties of food, but also places large quantities of food with very low nutritional value on the market. “The food that is being put on the market today,” notes Nadia El Hage, “is not of the same quality as before the Second World War; compared to more than 60 years ago, most crops have lost, on average, almost 20% of nutrients with peaks of up to 70 or 90%.”

The food we consume is therefore increasingly nutritionally deficient and potentially harmful to human health as a result of the large quantities of pesticides and chemical fertilizers used in the productive process. “This non-ecological approach to food production”, the Manifesto reports, “coupled with unhealthy food processing and commercially obsessed manipulative marketing practices, has created propulsive pathways for disruptive diets that produce ill health. The food processing phase also appears particularly delicate, considering the addition of large amounts of chemicals.”

Food transformation is a process that accounts for about three-quarters of all international food sales. Healthy substances, such as vitamins, are generally removed and large amounts of sugars and fats, preservatives, organic solvents, hormones, colouring agents, flavour enhancers and other food additives are normally added, especially when the food has to travel thousands of kilometres and must be processed to increase its shelf-life. The effects of these additives are often unknown, while their interactions with other substances present in food have not yet been identified.

The authors of the Manifesto affirm that these types of diets, rich in calories but poor in fibers and nutrients, together with high fats, sugar and salt intake are associated with a large part of NCDs, caused by biological risk factors such as: high blood pressure, high blood sugar, high blood lipids and body fat, which in turn trigger pathological processes of inflammation, atherosclerosis of blood vessels, thrombosis and induce carcinogenesis through epigenetic effects. To continue along this path, the Manifesto concludes, is to be considered “immorally indefensible” and in a final analysis, could not be defined in other words if not as a failure of our civilization.

Pesticides: these unknown

At this point, a question arises spontaneously: when we buy and consume industrial food on a daily basis, are we actually feeding ourselves or are we rather poisoning ourselves? And above all, are we really informed about the origin and content of the food we eat and therefore free to choose what is best for our health?

Unfortunately, the choice is not just up to us. On the contrary, in many cases, our choices are influenced by incorrect or partial information that does not make explicit what the risks associated with poor nutrition are. Providing information about the actual risks and putting the choice in the hands of consumers and farmers are some of the main objectives of the “Food for Health” Manifesto.

The issue of pesticides is emblematic because not everyone is aware of their harmful effects on the environment and human health. Yet this is no breaking news. As early as 2006, the scientific journal The Lancet published a list of 202 toxic substances, including 90 pesticides, which are particularly dangerous because of their potential negative effects on the human brain. Subsequent research has confirmed the risks associated with the use of agrotoxins for the human body as they can induce multiple and complex dysfunctions in all organs and systems, thus leading to endocrine, nervous, immune, respiratory, cardiovascular, reproductive and renal diseases. Pesticides can come into contact with people in different ways, through the air or by direct skin contact, but the greatest exposure occurs through what we eat and drink. This is a risk for adults and children, but also for infants who are indirectly exposed to dangerous chemicals through the placenta or by breastfeeding. It has been observed that for children in particular, there is a greater chance of cognitive impairment and an increased risk of contracting cancer, especially leukaemia and lymphoma, when exposed to these chemicals.

In short, it seems that the time has come for us to use the extensive scientific literature in our possession to expose a toxic production system and call for an immediate paradigm shift, as Patrizia Gentilini, member of ISDE Scientific Committee (International Society of Doctors for the Environment) and one of the authors of the Manifesto, argues: “The time has come to stop lying to workers and citizens, and stop claiming that cancer is caused by mere fortuity; our studies show that cancer is caused by environmental factors, and that pesticides increase the risk of contracting it.” Although health risks are very high, they are also little known, when we consider the absence of any kind of biomonitoring on our territory. And it is not only about cancer: “There is now evidence of a strong correlation,” adds Dr. Gentilini, “between exposure to pesticides and the constant increase in diseases such as cancer, respiratory diseases, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), autism, attention deficit and hyperactivity, diabetes, infertility, reproductive disorders, foetal malformations, metabolic and thyroid dysfunctions.”

One of the main warnings raised by the scientist, is that pesticides behave as endocrine disruptors. “Concerning endocrine disruptors and carcinogens,” Gentilini stresses again, “there are no safety limits.” Therefore, the so-called “safety thresholds” seem to have no value, as confirmed by the latest report of the Ramazzini Institute that shows how glyphosate, the active ingredient of some of the most widespread pesticides used in agriculture, is still toxic even at the so-called “safe” doses. Glyphosate-based pesticides, regardless of dose and exposure time, can alter some important biological parameters, in particular, sexual development, genotoxicity and the intestinal microbiome.

There are therefore no “safety thresholds” when it comes to pesticides which, even at low concentrations, can cause serious damage to human health. But the risks are not limited to the individual substances that are released into the environment. Pesticides that can be purchased on the market are in fact composed of both an active ingredient and its adjuvants which, in many cases, are even more dangerous than the active ingredient declared by the manufacturers. It is essential to point out that the current toxicological assessments only cover the active substance declared by the manufacturer. The toxicity of the adjuvants, including preservatives, thinners, emulsifiers, and propellants are likely to increase the toxicity of the product and are not taken into account by the competent authorities. They usually base their evaluations exclusively on the documentation made available by the manufacturer, without carrying out any adequate independent testing. What the institutions responsible for the control and authorization of hazardous substances do not consider, or do not want to consider, is the so-called cocktail effect, i.e. the interaction among the various chemical substances already present in the environment, as well as within the individual product placed on the market.

The result of this “scientific” authorisation procedure is easily ascertained: the consumer, who trusts the institutions in charge of controls, and who is unaware of the flaws of the current authorisation procedures, is led to consider the final product placed on the market as safe. A real sleight of hand, therefore, where reality is hidden behind reassuring labels that contain partial and inaccurate information. A dangerous game where we have unconsciously placed the most risky of bets: our own health.

Between propaganda and false myths: the poison is served

Is the current massive use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides really necessary to increase production? Is it indispensable to feed the growing world population or is it instead beneficial only to the interests of big agribusiness corporations? There is extensive literature available that exposes how manufacturers feed propaganda to continue to sell their products, notwithstanding the fact that they are harmful. Advertising, as we know, is pervasive and convincing, certainly more than the body of scientific literature that has been dealing extensively with the actual effects of agrotoxins on the environment and on human beings. In order to shed some clarity on the subject, it is sufficient to consult the latest UN reports, starting with the contribution of Hilal Helver, UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, and among the authors of the Manifesto. According to Helver, the problem of world hunger is related more to poverty, inequity and food distribution, rather than to production. Moreover, Elver has denounced the indiscriminate use of pesticides as it is directly related to 20,000 deaths from poisoning, a year, worldwide. Along the same lines, according to the estimates of the WHO and UNEP, there are at least 26 million cases of pesticide poisoning in the world every year that, in many cases, lead to death.

These figures are worrying but not surprising, considering the fact that chemicals cover the entire food supply chain, from field to table, where they are present not only in fruit and vegetables but also in meat, fish and dairy products. Indeed, exposure to pesticides can occur in many ways, including direct exposure, particularly among workers involved in pesticide production, sellers and farmers who apply them in the fields. The processing stage is also responsible for the contamination of our food with plastics, preservatives, organic solvents, hormones, flavour enhancers and other food additives introduced into the food at this stage.

Exposure also occurs through residues in surface water from agricultural runoff, contamination of wells and groundwater, and wind dispersion from aerial spraying. In short, you don’t have to live only a few meters away from an intensive monoculture farm to start worrying, as confirmed by a recent pilot study on soil contamination, conducted by the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission and the University of Wageningen. According to the study, traces of pesticides were found in more than 66% of the samples analyzed. The most commonly detected substances are glyphosate (46%), DDT (25%) and fungicide products (24%) which, it is noted, can be concentrated in very small soil particles, which are easily eroded and transported by wind and water, carrying the risk of contamination even over long distances.

These data seem to be confirmed by the latest National Report on pesticides in waters by ISPRA, the Italian Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale, which detected approximately 259 different toxic pesticides in Italian waters. Pesticide residues were found in 67% of monitored surface water and in 33.5% of groundwater, with an increasing trend compared to the same survey performed in 2003. According to ISPRA, glyphosate, together with its metabolite AMPA, is the most present herbicide in Italian waters: both substances, as recorded in the ISPRA report, are higher than the value allowed by the regulation on environmental quality standards for water (EQS) at 24.5% and 47.8% of the monitored sites for surface water, respectively.

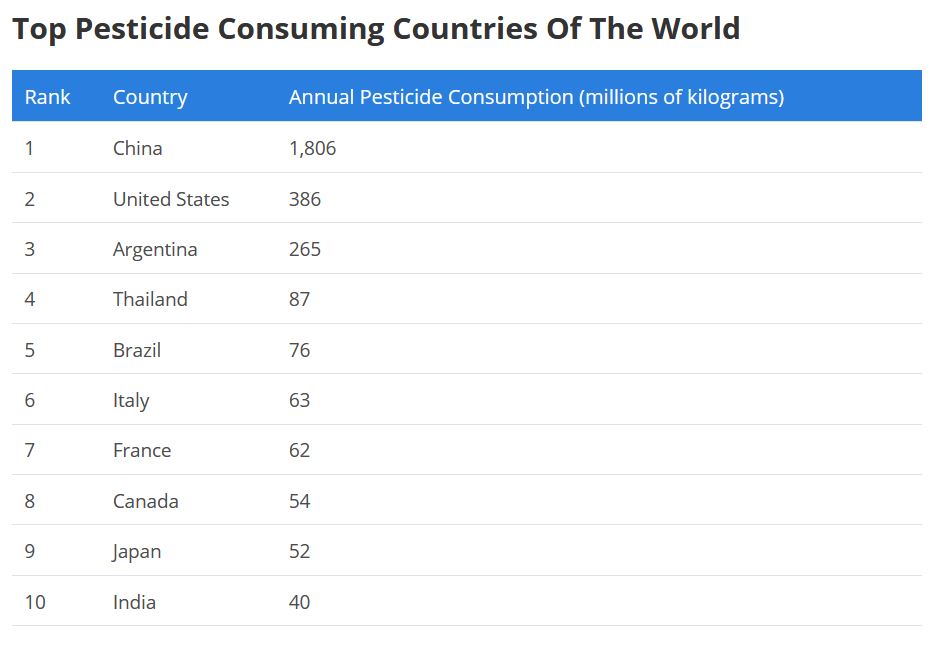

Even if it is true that agrotoxic spraying in Italy exceeds 5 kg per hectare – the highest percentage in the EU – it should be noted that the Italian data do not differ much from those of the rest of the world. Among the largest consumers of pesticides in the world is China, with 1,806,000 tons per year, followed by the United States with 386,000 tons per year, Argentina at 265,000 tons, Thailand at 87,000 tons, Brazil at 76,000 tons,. While Canada, with which the European Union has recently signed the controversial CETA trade treaty, stands out with about 54,000 tons per year. In this special ranking, Italy stands at a prominent position with 63,000 tons per year, more than the annual consumption of India, at 40,000 tons.

Source: World Atlas

According to the latest FAO and IWMI report, More People, More Food, Worse Water? A Global Review of Water Pollution from Agriculture, industrial agriculture is the primary contributor of groundwater pollution in the world. The report confirms how the massive use of pesticides and fertilizers contributes to the contamination of groundwater, endangering human health and that of the planet. In fact, industrial agriculture is responsible for 96% of ammonia emissions into the air which, reacting with other pollutants, produces a very dangerous fine particulate matter. In short, this should be enough to change the productive model immediately and yet, the introduction of dangerous substances into the environment does not seem to stop. On the contrary, according to the FAO report, the use of fertilizers is destined to increase by 58% by 2050. This is not good news, considering that today 4.6 million tons of chemical pesticides, including herbicides, insecticides and fungicides, are spread annually on agricultural soils, and that at a global level, every 27 seconds a new chemical is synthesized. Beyond myths and corporate propaganda, the results of scientific analysis from laboratories all over the world seem to agree across the board, confirming the urgency expressed in the Manifesto: that we cannot have any more poisons on our tables.

It’s time to switch production models towards a healthy, poison-free diet

In the area of good nutrition, how important are personal choices in living a healthy life? They are certainly very important, but it must be recognised that we are not always free to make the right choices. Our choices are conditioned by many external factors which actually make them less free than we might think. The processes of food standardization, along with aggressive marketing, misinformation, lack of transparency in the supply chain, as well as the available market supply and price policies imposed by oligopolies, are some of the factors that condition our ability to choose freely. For this reason, the “Food for Health” Manifesto is not only directed to individual producers and consumers but also to governments, which are responsible for the welfare of their citizens and are custodians of their rights. Cooperation between citizens, farmers, universities, researchers and institutions appears to be an essential element for a paradigm shift.

An urgent transformation without compromises is necessary, as Patrizia Gentilini points out: “We can protect our health through the food we consume and by having access to healthy food, rich in all those nutrients and substances which protect our health and, as much as possible, free from dangerous residues, be it environmental contaminants, or residues from chemical agriculture, especially pesticides. The time has come for us to change the agriculture model and, as we always stress, talking about sustainable use of pesticides is an oxymoron, because pesticides are poisonous and toxic substances, designed and studied to cause damage to other forms of life and therefore they are obviously dangerous for us too.”

The extractive, polluting and linear production system must then primarily be replaced by a circular economy that respects people’s rights and the environment. Our own planet works in a circular way and could soon be brought to exhaustion should the current linear production system not be reversed. Many good practices have already been tested and they show that alternatives do exist and can be put in place, regardless of the political will. This is the case with short supply chain production systems and zero km farmer’s markets that have demonstrated viable solutions to food waste, greenhouse gas emissions, ecological footprints and wealth disparities. Small and medium local producers can also play a major role in the conservation of biodiversity, and thus in enriching our diets, by conserving indigenous seed varieties and protecting them from agricultural markets flooded with expensive seeds owned by multinationals.

Supranational organisations can also play a key role in stimulating change. This is the case of FAO, which has recently recognized that agroecology contributes directly to some of the most important Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including ending poverty and hunger, ensuring quality education, achieving gender equality, increasing the efficiency of water use, promoting the creation of decent jobs, ensuring sustainable consumption and production, strengthening climate resilience, ensuring the security and sustainable use of marine resources and safeguarding biodiversity.

Agroecology, intended as a vision of life based on the concept of integration between mankind and nature, can give impetus to a new productive model that preserves biodiversity and promotes environmental sustainability: “The FAO,” stressed Ruchi Shroff, Navdanya International’s director, “has recognized the importance of farmers’ traditional knowledge and the crucial role they play on the front of food security. What small producers and consumers must reclaim is a new agricultural and economic paradigm, a culture of food for health, wherein which ecological responsibility and economic justice take precedence over today’s consumption and profit-based extractive productive systems.”

It is therefore time to enter a phase of transition from an industrial agricultural model based on competition, to a regenerative ecological model based on cooperation and ethical use of new technologies. In the unmasking of the economic interests which manipulate knowledge and science in order to hide the real costs of their activities and extend market control, our food and therefore our health, is only the first step needed if we want to rebuild a knowledge system based on the defence of biodiversity and the common good. This is an epochal and necessary step to reclaim our democratic rights and stop the drift that is threatening to bring the entire planet to collapse. The “Food for Health” Manifesto is a reference tool for all agriculture and food stakeholders and for ordinary citizens who want to be informed by understanding the real interests behind current food production policies, and finally engage directly in a civil movement for a paradigm shift based on the rights of the environment and human beings. Because, as Vandana Shiva so fondly recalls, “the health of people and the health of the planet are one in the same.”

Translation kindly provided by Arianna Porrone, Elisa Catalini, Carla Ramos Cortez

The original article was first published in Italian in Terra Nuova magazine, September 2018