By Manlio Masucci, Navdanya International

Intensive monocultures of hazelnut groves are sweeping across Italian regions to meet growing corporate demand, while also feeding doubts regarding their environmental and economic sustainability. Organic providers, local governments, scientists and citizens are mobilizing for an eco-sustainable production model and the development of local supply-chains to deliver real prosperity to their communities.

From Tuscia to Valdarno, crossing Umbria and Marche. There are many Italian regions in which the expansion of hazelnut cultivation looks unstoppable. The industry is supposedly very lucrative, considering the high demand for the primary product fed predominantly by several corporations in the confectionary sector, such as Ferrero, Nestlé and Loacker, who are prepared to offer producers enticing supply contracts. But criticisms regarding this model are emerging from many quarters. Particularly from the area in which the ‘Biodistretto della Via Amerina e delle Forre’ bio-district lies, which currently covers 13 Tuscian municipalities. It is fighting on all fronts, pitting itself against the invasion of intensive monocultures with high chemical inputs. A system, so read the charges filed, with a high impact on the landscape, on the soil and on potable water; on the health of the inhabitants of rural areas, on agricultural workers, on tourism, on biodiversity and on the organic crops themselves. The Bio-district’s raison d’etre is to prove, in cold, hard facts, how an ecological approach to hazelnut cultivation could foster a more sustainable and equitable economic model. The issue of the hazelnut is becoming a relevant one. It begs the comparison, and often the confrontation, between two worldviews: that of the globalised economy, based on the exploitation of resources, on long supply-chains and on large-scale distribution, and that of the valuing of the local economy and of the food sovereignty that are based on respect for the earth from environmental, social and cultural perspectives.

Stink-bugs are the most feared pests in hazelnut cultivation

Environmental conflicts

It is Tuscia which constitutes the crucial frontline of a conflict that seems on the verge of spreading to other areas of the country. The region, where the problems related to this intensive cultivation are more obvious, is now turning into a laboratory where it is possible to assess both the magnitude of the conflict and the potential of alternative models. These alternatives are based on organic farming and on the involvement of all local players within ethical economic circuits. This is, for instance, the objective of the ‘Biodistretto della Via Amerina e delle Forre’ bio-district, which, for almost ten years, has been trying to push the case for environmentally responsible agriculture in an area recently placed under the monitoring of CDCA, the Centre of Documentation on Environmental Conflicts.

“We are not against the hazelnut business, but against the means of production and processing,”,” so explains the Bio-district’s president, Famiano Crucianelli, “because one of the hazelnut’s important roles is in the economy of the community which serves merely as a ‘colony’, churning out a primary product. An extractivist model which can damage the land with pesticides, herbicides and chemical fertilisers, while the harvested product is then sent to processors in Piedmont and France. In the long term, we could have a land depleted of its fertility and serious harm to primary resources such as water. Tuscia is an area of stunning natural beauty, where it is possible to enjoy the precious legacy of Italian history and culture. Intensive hazelnut cultivation is putting this extraordinary heritage at risk.”.

One need only glance at the data to fully appreciate the scale of the phenomenon. According to Coldiretti, hazelnut cultivations are being established across practically half of Tuscia, encompassing 30 municipalities and 8 thousand families. Approximately 30% of Italian hazelnut groves are found in the Viterbo province. The invasiveness of the monocultural model has led, in some cases, to veritable infestations, with municipalities who have planted 1,600 hectares of hazelnut trees on an overall space of 1,800 hectares. The rapid expansion of the hazelnut business has caused important changes to the social fabric, too, by facilitating the concentration of private ownership and the industrialisation of the sector. Small-scale producers are disappearing while private businesses drain the earth in their hunt for new plots of land.

But why this sudden ‘hazelnut rush,” so overpowering as to transform the characteristics of a land rich in history and culture in a matter of a few years? In this neck of the woods, the hazelnut business is linked primarily to the Italian corporation Ferrero, which offers an enticing contract to producers with the pledge to buy up 75% of the production of new plantations for twenty years without ruling out the purchase of the remaining 25%. And the proof that such a model works perfectly for business is confirmed by the ‘Nocciola Italia (Italy’s Hazelnut)’ Project, launched by Ferrero in 2018, which envisages the development of 20,000 hectares of new groves at the national level (a 30% rise from the current coverage), with the overall aim of gradually increasing production to 90 thousand in all of Italy.

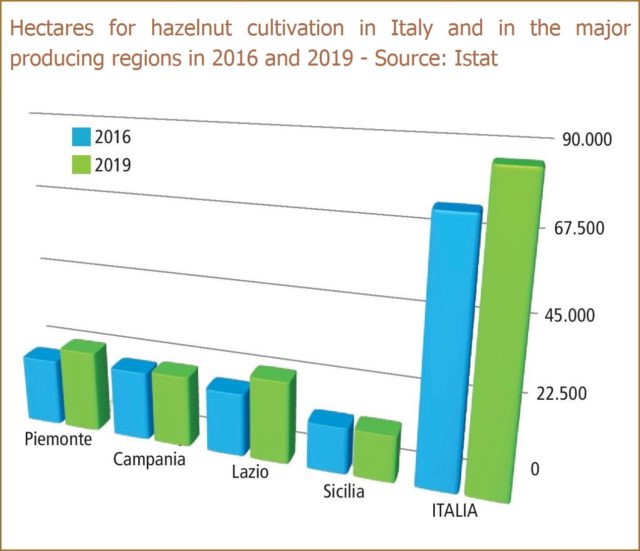

An objective which has almost been fulfilled, bearing in mind that, in 2019, the area of land under hazelnut cultivation in Italy reached 86,725 hectares according to ISTAT’s findings, around 13 thousand hectares greater than in 2015. Furthermore, Ferrero’s proposal appears difficult for many private setups to refuse, especially those who want to make an income from their plots and do not have comparably reliable alternatives on offer.

There is a catch, however, considering that stink-bugs represent the number one threat to these crops: the product must show an almost non-existent percentage of stink-bug damage. But does this demand for a bug-damage rate close to zero make sense? Is it really so important that the hazelnut should look practically untouched, and be almost perfect?

“It’s madness”, Mario Profili, from the organic enterprise Lucciano, complains. “In the first place because we are talking about almost imperceptible imperfections in the product and secondly, because in order to achieve that result you are basically forced to use pesticides. The battle against stink-bugs must instead be fuelled and maintained by a high biodiversity rate. Stink-bugs prefer fields and plants, but when they don’t have another option, they attack the nut. We don’t treat our crops: however, through maintaining a high biodiversity rate, we have very few problems with pests and we actually cut the grass very late in order to offer them an alternative habitat to the crop. In organic farming, the objective is not destroying the parasite, but containing it. As a result, we have a very low bug-damage percentage“, Mario concludes, “below 10%, which allows us to produce spreads of the highest quality.”

To summarise, in the conventional agricultural model, fertilisers are used to make the nuts grow to excess, then come the herbicides to dry out the infected grasses, which would normally be the stink-bugs’ favourite meal. Finally, the pesticide treatment begins when the parasite shifts onto the trees. It’s a massive injection of chemicals solely for the purpose of lowering the percentage of bug-damage by a few points without even questioning whether this demand is logical and thereby justified.

It is not a coincidence that the bio-district’s strategy also focuses on raising the permissible percentage of stink-bug damage. If such percentage markers were to be raised, even if by a little, there would no longer be the need to resort to chemicals. Also, because the more groves that are cultivated with chemicals, the more those organically cultivated will be targeted by the pest, “It is clear that an organic hazelnut tree surrounded by ‘conventional’ ones is certain to die”, Mario Profili goes on to note, “as the stink-bug naturally seeks shelter on untreated plants. Many organic farmers have actually had to change to conventional methods for this reason. Vice-versa, if the groves were all organic and natural balances were respected, the stink-bug problem wouldn’t be present.”

The confrontation between conventional and organic agriculture is taking shape as a true battle of no mercies, which is rupturing the social fabric of the region, pitting citizens and farmers against each other.

“An unparalleled polarisation,”,” as Stefano Liberti has recently commented in the magazine Internazionale, ‘which is in danger of leaving a very deep scar in one of the most beautiful and most bountiful areas of Italy, whether viewed from a natural or a cultural perspective.”

An organic hazelnut grove at the Lucciano farm in Civita Castellana. Photograph by Manlio Masucci.

Sustainable organics

In short, conventional agricultural methods damage organic farmers by directly impacting production. This is not news, but are we convinced that conventional agricultural methods, excluding economic damage dumped on the community as a whole, are as profitable for farmers as the industry claims? Indeed, chemical treatments have high costs- whether its for the pesticides needed or for the necessary labour cost necessary for their application. Then there is the cost of increased irrigation, especially considering that a treated plot is thirstier than an organic one. A ‘drugged’ production model can also lead to considerable results in the first few years, namely in the short term, but what happens in the mid-long term when the plot loses its fertility?

The organic hazelnut grove on the Lucciano farm, 28 hectares planted almost 40 years ago, seems to offer precise answers to these questions. The output of the organic business amounts to around 2500kg per hectare: a figure very close to that produced by conventional methods. An organic hazelnut, however, earns much more on the market, around 350 euros per 100kg as opposed to around 250 euros per 100kg for the conventionally produced hazelnut.

This naturally begs the question of whether the demand for organic products is high enough. Are consumers prepared to pay that extra bit more for a genuine and healthy product? We put this to one of the very few radical businesses in the district, Deanocciola, which has always worked following organic methods and processes the shelled nut on site. “Organic products can cost up to 40% more than conventional ones,” Manuela De Angelis, manager of the company, confirms, “but the consumer is prepared to pay a higher price in exchange for peace of mind. The organic sector is growing exponentially because everyone reads the label these days, and the shorter the list of ingredients is, the more assured the consumer feels.”

Investing in knowledge seems to pay and the company, beyond not using palm oil, actually refuses to include stink-bug damage in its quality criteria. The purchase of a first-choice shelled nut takes place independently of unsustainable bug-damage percentage markers and without shackling producers to unrealistic standards that are achievable only through the employment of chemicals.

A utopian model? The experience of De Angelis’ company demonstrates how a localised economy, attentive to the valorisation of typical products such as the ‘gentile tonda romana (sweet round Roman)’ hazelnut, is both possible and sustainable. The company, established in the 80s, now employs 27 people and has not hit a crisis due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, not only has it avoided resorting to the governmental lay-off scheme funding, it has had to double its production shifts to meet the growing demand coming predominantly from Europe. No supply issues, and growth margins which are significant evidence of how medium-sized, Italian businesses could offer an alternative solution to the extractivist theorem of the big corporations.

Success experienced by producers on the ground are reinforced by numerous scientific studies, as Roberto Mancinelli, professor at Unitus’ Department of Agricultural and Forest Sciences, explained at a recent conference concerning hazelnut groves. He outlined a specific comparative study between the economic performance of organic and conventional farming, conducted on 55 crops cultivated in 5 continents over 40 years (Crowder and Reganold, PNAS, 2015).

“Rendering agriculture financially viable,” Mancinelli highlighted, “is essential, but it is only one of the four objectives that must be reached by agriculture in order to become sustainable. It turns out that organic farming is more advantageous economically, even if it generates lower yields compared to those offered by conventional farming, because it entails higher standards and benefits relating to human health, the environment, and socio-economic factors.”

Furthermore, in the age of climate change, climate resilience should occupy a central place in local food production strategies. And yet we are still witnessing the expansion of monocultures based on blind faith in corporate buying power, which operates through a monopoly system. “The corporations don’t bring benefits to farmers,” Mario continues, “quite the opposite: the agro-industry has always exploited us. This is the history of the farmer’s lot; we are also subject to natural events and we must be ready for changes with multifunctional businesses that guarantee the survival of productivity and employment. We have big opportunities to make a different economy if we do not structure ourselves exclusively around one product, yet there are entire regions which only cultivate the hazelnut. The survival of the earth cannot depend on 2-3 corporations from the confectionary industry, nor can it base itself on a single cultivated crop. Above all one cultivated in such a way.”

In the case of the Lucciano enterprise, the alternative model seems to work marvels with the diversification of production as well, which allows the company to deal with market fluctuations. The organic enterprise, covering a total of 120 hectares, is founded on the concept of the closed-loop system and employs 16 people in total. In this case, too, the damage caused by COVID-19 has been minimal and redundancies have been avoided.

The Lucciano enterprise is one of the founders of the Bio-district, which was created to generate knowledge and put pressure on institutions so that they protect the land.

Proposals are offered and not just protests, then, with the objective of offering the region a holistic vision which puts agriculture, culture and tourism in collaboration with one another. And the pilot project, which takes its name ‘The Hazelnut Community’ from this vision, is in the launch stage, with eleven organic companies covering almost 300 hectares, ready to put themselves out there in support of sustainable development. The aim is to demonstrate how a local supply-chain, from the production stage, up to processing and to marketing, could work better than a monopoly which exerts absolute control over prices.

Monopolies are a risky dependency, as Carlo Petrini has also indicated. “In the next few years, with trebled production, we risk lower quality, lower sustainability, less diversity in production and a bigger dependency on a sole buyer who decides the prices. If the hazelnut becomes a commodity in Italy, the big industries will sort the business matters, but the farmers will have to content themselves with watered-down prices.”

A conscious agriculture?

The little old world of conventional farming, due to its unsustainability, is bound to leave a space for a new model of economic development. But resistance to this paradigm shift is still strong, considering the big business interests and the related supply chain involved. The attitude held by shareholders, relatives, friends and associates is that the overwhelming majority of the local population is in some way involved with the hazelnut. A business that it would do better to leave be, in order not to ruffle any feathers. Even the conversion to organic, fostered by the Bio-district, is becoming vague and uncertain in these areas. The first hurdle in the analysis of what is happening in Tuscia emerges in simply understanding who is really working in the organic sector. If there a true organic and a false one?

A confusing idea, but an accurate one, according to the president of the Bio-district, Famiano Crucianelli. He reveals how many farmers request 5 years’ funding for the transition to organic, just to then revert to conventional methods when the plan reaches the production stage. A loophole that may be unethical but is also perfectly legal. “It is unacceptable,” Crucianelli strikes up, “that they are using organic resources not to produce organically, but only to expand their conventional enterprise. One of our demands is to bring the bond up to 10 or 15 years.” Crucianelli refers to the 2014-2020 Rural Development Programme of the Lazio region, a 780 million-euro plan, which provides for a contribution of 900 euros per hectare per year. The plan, approved by the EU for Lazio and Umbria, receives European funds to support the transition from conventional to organic methods. In 2015, the Lazio region signed an agreement with ISMEA (the Institute of Services for the Agricultural Market) and Ferrero to plant 10 thousand new hectares of hazelnut groves.

Between those who farm conventionally and those who farm organically there exists, however, a middle ground. It is that of conscious agriculture, which is nothing other than the rigorous application of integrated farming methods whose directives are all too often disregarded. In the case of conscious agriculture, it is the municipalities who take control of the situation and decide when and how the groves can be treated. A fixed calendar and stringent control from authorities take the place of the cowboy tactics which circumvent agrochemical restrictions. It is a model for transition which aims to reduce the quantity of pesticide applications, at the very least.

An additional impact of the Bio-district’s campaigns, other than having obtained a drastic reduction in the use of glyphosates and similar chemicals, is that it has also won a victory on boundary compliance. The security distance for limiting chemical drift effect is 15-25 metres in almost all the region’s municipalities. Putting the use of pesticides under tight control, be that from a quantity, type or methodological point of view, the model offered by conscious agricultures appears could possibly be a transitional one. A method which could soon be transferred to the Cimini region as part of a partner project between the Bio-district and the Regional Agency for Development and Innovation of Lazio (ARSIAL). The positive experience of the Corchiano municipality acts as the figurehead for the conscious agriculture route. Almost all of the municipalities have written the rigorous pathway of integrated agriculture into their by-laws, but, even in this case, administrations should take note of who decides to contravene by-laws and municipal reports, starting up tractors in the dead of night to spread toxins far from prying eyes. If we add to this phenomenon that of the shift from organic to conventional after the first five years, we realise that the road to transition seems thoroughly bumpy and exploited by ‘sly foxes’ who risk nullifying the efforts made by institutions and organisations in defence of the land.

Hazelnut monocultures in Capodimonte (Viterbo), on the shores of Lake Bolsena. Photograph by Lake Bolsena Association.

The ones who say no

Violating the rules, or circumventing them, shows how the fight for the land is also and chiefly a cultural issue. It is worth highlighting, though, that many doubts are also beginning to spread among conventional farmers. This is the case for Giuseppe, who has recently decided to leave the economic security of conventional methods behind to convert his entire 15-hectare hazelnut plot to organic. A choice motivated by environmental considerations but also economic ones. “The decision to quit conventional farming? First of all,” Giuseppe explains to us, “because I didn’t want to use pesticides any more. I was tired of breathing in toxins and collecting dead birds whenever I went into my fields. Reaching a stink-bug damage rate lower than 3% was practically impossible, it meant having to constantly drench the fields in chemical products; in the meantime, organic techniques evolved and we manage to get a good profit even with a bug-damage rate between 10 and 15%, maybe even higher than a conventional farming profit.”

Although Giuseppe has decided not to renew his conventional contract, he does not have a bone to pick with his colleagues who have chosen to stay put. “I understand the farmers who stick with conventional methods. They accept a legitimate proposal from parties who guarantee them the immediate sale of their product and are not interested in going organic. Getting out of this system was my choice, prompted by the fact that this type of contract makes the farmer so dependent. You are obliged to sell the product exclusively to the one buyer, with an often questionable quality standard as the assessment is conducted by that same buyer. The quantity standards are stringent, too, with really precise production quotas which, if they are not reached, can trigger penalties. I have never received any type of pressure, only strict conditions which, at a certain point, I didn’t want to meet any more.”

Giuseppe’s dream is still to see his land develop thanks to the value of the hazelnut. “We must be capable of promoting the local supply-chain, from the production stage through to processing and marketing, and making this the best option. Farmers don’t have many alternatives and in the majority of cases they are forced to resort to these big, dominant businesses to get rid of their product quickly and secure a reliable income.”

The valorisation of the land also manifests through the preservation of the landscape and native crops. Interest in the phenomenon of hazelnut cultivation from the Supervision of Archaeology, Fine Arts and Landscape did not spring up by chance. A circular letter sent to the Lazio region, Viterbo province and to the municipalities of Tuscia outlines that landscape authorisation will be necessary for the planting of groves in areas recognised as landmarks of archaeological interest. This is in response to the capacity of hazelnut monocultures to effect ‘a certain modification of the identifying characteristics of the rural and land landscape,” through deep trenching, often involving trenches much deeper than a metre, and the replacement of traditional cultivations such as that of the olive.

Local administrations are therefore called to play their part, but their measures are not always effective, not least because of the resistance from landowners and from their associations, ready to turn against municipal ordinances. This is the position of the mayors of the towns surrounding Lake Bolsena, who are trying to protect the water basin from potential contamination. The recent ordinances from the mayors of Bolsena and Grotte di Castro have not, however, had a positive outcome, and were voted down by Lazio’s Regional Administrative Tribunal (RAT).

A victory for the monoculturists capable of triggering a cold feet effect in other administrations who originally wanted to protect the land? More akin to an assessment error, according to lawyer Ottavio Maria Capparella, head of the Accademia Kronos legal office, who underlines the “massive procedural flaws and the incorrect set-up” of the measures. The two ordinances actually prohibited the planting of new hazelnut groves on common land regardless of cultivation methods, thus impinging on the right of private economic initiative. The legal team emphasises that nothing prevents the municipalities from re-submitting the ordinances, avoiding procedural errors and attaching adequate scientific evidence on the observed dangers for the population and for the environment.

The demand and intention for creating a national network on this issue was established during a recent conference held in Tolentino at a meeting of several associations from central Italy involved in the fight against monocultures. It would be capable both of embracing the different associations from Tuscany, Lazio, Umbria and Marche, and of making their voice heard at the national and European level. A round-table discussion with all the interested parties will take place in Orvieto in the next few months.

See below a list of the organisations involved in the network: Biodistretto Via Amerina, Bolsena Forum, Osservatorio del Lago di Bolsena, Bleu – Bolsena lago d’Europa, Comunità Rurale Diffusa, Comitato 4 Strade, Pratomagno, Progetto Nocciola Italia No Grazie, Slow Food Valdarno, Seminterrati.

Such was the approach pursued by the Montefiascone municipality which, in May 2019, published a ‘dissuasive’ ordinance that did not expressly prohibit the planting of new groves, but placed a series of conditions which effectively made it extremely difficult to do so. For example, the restrictions involved fines which, in the case of a transgression, would reach up to 20 thousand euros. Beyond a tight grip on the use of pesticides, including the total banning of glyphosate, landowners will have to undergo an impact assessment from the same municipality that aims to make them apply the dictates of integrated agriculture to the letter. It specifies that the ordinance is valid whether for groves that are already planted, or those yet to be so. A more pragmatic approach, then, which seeks to favour a transition phase that respects constitutional rights and positions the municipality safely apart from legal disputes.

This is the legal strategy drawn up by the lawyer Capparella. But why has the Lazio RAT not voted down the Montefiascone ordinance, as it has done for those issuing from other towns? “Because the ordinances were written separately,” Capparella points out, “without a real discussion between municipalities: in the case of Montefiascone we respected constitutional profiles, cognizant that we cannot forbid private firms’ liberty of choice, but what we can do is to erect a series of obstacles in defence of the land to make the planting of new cultivations with a high environmental impact, more complicated. It is simply about reclaiming the rigorous application of existing laws, while referring to the precautionary principle.”

Rita Chiatti, the environmental assessor and promoter of the measure, confirms that the Montefiascone ordinance could become a model for all those administrations who really want to curb the invasion of intensive hazelnut cultivation. She reassures us how the municipalities in the region who want to copy the initiative, such as in the case of Valentano, are numerous. “This measure,” Chiatti explains, “is the answer to the bottom-up citizen initiatives. I note in particular those of the associations Lago di Bolsena, Bolsena lago d’Europa and la Porticella, which are increasingly concerned by the condition of the land and of the subsequent risks that it could prompt. There are many municipalities in the region that we are in discussions with about copying the initiative with the aim not of stopping at that, but of founding a Bio-district.”

Therefore, the role of citizen associations has been fundamental in the defence of the land. The associations had already sent a letter to the Lazio region a year ago, with respect to the agreement with Ferrero, expressing the, “fear that Lake Bolsena will degrade as the result of intensive hazelnut cultivation, as the neighbouring Lake Vico did”. Recalling that the lake is recognised by the EU as a Site of Community Interest, a Special Area of Conservation and a Special Protection Area, and is thus a sensitive and protected area, the associations indicate how ARPA Lazio revealed that the ecological state of the lake has worsened over the last 15 years in violation of the EU’s framework directive on water. “The degradation,” so reads the associations’ statement, “is due in large part to nutrient pollution with sewage and agricultural origins, which causes the uncontrollable increase of aquatic vegetation and the consequent process of eutrophication.” To complete the picture, there is pollution from pesticides, an increase in hydraulic levies, global ecosystem degradation and the fact that the potable water network is fed by the same aquifer as the lake. “The hazelnut grove project, if followed through,” the statement continues, “would involve a general deterioration of the ecosystem, nullifying every effort for the restoration that it needs, by sentencing to a subsequent and irreversible degradation, which would lead to heavy penalties for embarrassing environmental offences by the European Commission.”

The Alfina plateau: new hazelnut plots. Photograph by Comitato Quattro Strade.

A ‘turnkey’ hazelnut grove: Umbria, Marche and Tuscany

The situation in Tuscia seems to represent an important precedent for deterring consortia and administrations in other Italian territories from giving new plantation plans a free pass. This is the case for the hazlenut’s Calabrian Consortium which refused Ferrero’s proposal, explicitly criticising a model which, based on very large monocultural stretches, favours quantity over quality and takes the product away from the land to process it elsewhere. “Our choice,” so reads the Consortium’s press statement, “is for quality, and for a processing of the product which needs to happen right here, allowing enterprises to structure themselves and the land to retain its own identity.”

On the other hand, the mayors’ ordinances alone do not seem able to stem the flow of the powerful currents which, when confronted by an obstacle, naturally switch direction. The residents of the Alfina plateau in the Orvieto province know something about this. They have seen bulldozers arrive from one day to the next to prepare the plots for new groves. A “shot to the heart” as Gabriele Antoniella from the Comitato Quattro Strade testifies. This committee was created precisely in order to bring citizens together against that which they themselves define as an exercise in land-grabbing. “Over two hundred and fifty hectares fenced off in two months,” Antoniella recounts, “with enormous holes to accommodate the crops without anyone having been informed and without the municipality having moved a finger, if it hadn’t been for the warnings we distributed following obvious violations. A true attack on the land from investors coming from the Viterbese area who, evading every restriction, are changing the landscape. They could even put water resources at risk if they use inappropriate agricultural techniques, bearing in mind that the underground aquifer layers supply, among others, the city of Orvieto itself. We are calling on the municipality,” Antoniella concludes, “to ditch the ambiguity and not to limit itself to responding to our requests, but to follow the example of so many other municipalities who have adopted a tight approach towards safeguarding their areas, by enforcing, in the first place, the laws that already exist.”

The issue of the Alfina plateau has also, however, attracted attention from representatives from the cultural sector such as the film director Alice Rohrwacher. Rohrwacher has recently published a letter sent to the governors of Lazio, Umbria and Tuscany, as well as to national organisations such as WWF and Italia Nostra, putting forward formal injunctions recalling, “how the entire area was designated by the urban development plan of the Orvieto municipality to become a Cultural Park and how every activity which entails changes to the landscape is forbidden.” Adding fuel to the fire is the announcement from the consortium of agricultural producers, Pro Agri, which provided the first regional supply chain agreement with Ferrero. The aim? To reach a coverage of 700 hectares of new hazelnut plantations in Umbria by 2023. In this case, too, it is the bulletproof contract guaranteed by Ferrero which decides the fate of the land.

Ferrero’s overt aim is to expand the hazelnut cultivations beyond the four ‘classic’ regions (Piedmont, Lazio, Campania, Sicily): they have taken steps to draw up maps of the Italian regions best adapted to the cultivation of the hazelnut. Through rearing its head in the Marche region with the professed aim of adding another 500 hectares, the Piedmontese corporation has also outlined its next targets: Valdarno and Valdichiana. The local Confagricoltura department mobilised immediately, setting out in search of agricultural contractors available to take part in the ‘Nocciola Italia (Italy’s Hazelnut)’ project. This is the fruit of an agreement between the Confagricoltura trade association, Ferrero and Arezzo province’s agricultural cooperative, Co.Agri.A of Cesa, with the backing of Terranuova Bracciolini and Laterina Pergine Valdarno municipalities.

But in this case, too, the associations have gone on the warpath. The Association of Pratomagno Producers and Slow Food are among them, having recently condemned the project which allocated 500 hectares to hazelnut cultivation. They have firmly rejected the reassuring declarations of Confagricoltura Tuscany’s president, who denied the evidence of risk to the environment stemming from the agreement with Ferrero. “All the evidence is there,” the associations’ statement reads, “you just need to look at the data gathered in Viterbo: polluted water, degraded soils, a number of cancerous pathogens higher than the national average, a splintered social fabric, with citizens on one side and agricultural producers, themselves victims, on the other.” The aim of the associations and local producers is to foster a natural model of agriculture through the reinforcement of the already-existing Rural District.

Furthermore, the development of an organic model at the inter-municipal level could lead to the construction of a Bio-district. “The rural district of upper Valdarno has already drafted a programme for development,” comments Luca Fabbri from Slow Food Valdarno, “presented to the Ministry of Agricultural Food and Forestry Policies (MIPAAF) on the occasion of the Food District funding bid. The research project, which will be directed by Unifi Dagri, will produce guidance for the acknowledgement of GIAHS (the FAO’s Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System), a safeguarding tool for farmers, the culture, the landscape and the agricultural biodiversity.”

The wave of hazelnut groves surges through the country, but it is not just Ferrero. The Bolzanese corporation Loacker plans to manage, through direct and indirect ownership, around 3 thousand hectares of hazelnut groves in Italy. In 2018, Loacker launched a development project for new groves with the bank Intesa San Paolo, on around 2800 hectares in Veneto, Friuli VG, Tuscany and Lazio. A project which can be added to the ‘Nocciole in Toscana (Hazelnuts in Tuscany)’ project in the Maremma Grossetana, which was set up, with its first plantations, in 2014 and brought an estate of 170 hectares into development around Fonteblanda and one of 120 hectares in Roccastrada. And the demand for primary resources does not stop at the proposal of extending the supply chain to Umbria and Marche. In Loro Piceno’s vicinity, Loacker launched a project which could result in the planting of 150 hectares of groves. Here, too, the company’s agronomists met local contractors to propose an investment with a guaranteed contract of supply-chain which foresees the purchase of 100% of the product for at least 15 years.

A ‘turnkey’ hazelnut grove as the corporations themselves called it. Nestlé can also be added to the group of corporations intending to do business on Italian land as it has, in typical corporate style sketched out ‘its land’ in Perugia. An agreement signed with various local stakeholders envisages an increased production of the local variety of hazelnut (the Francescana Tonda) by 2023 to be able to coordinate with Nestlé starting up an industrial experiment for the production of the Bacio Perugina chocolate candy. The University of Perugia, Confindustria Umbria, Cia, Confagricoltura and Coldiretti catch the eye as being among the listed stakeholders.

The coverage of Italy’s land surface used for hazelnut cultivation has reached 86,725 hectares, around 13 thousand hectares greater than in 2015. In 2018, the professed target of Ferrero alone, which now siphons around 30% of world hazelnut production, was to increase Italian hazelnut production by a third, via the conversion of over 20 thousand hectares of land. A target which seems to be within its reach, thanks to the increase in hectares in the major producing regions and in the new plantations which are being added in regions such as Umbria, Marche, Tuscany, Veneto and Lombardy.

The issue of hazelnut groves, clearly, does not just concern a few distant and disconnected areas any more. Quite the contrary: intensive monocultures of groves are growing like spots of oil, squeezing past whenever they encounter an obstacle. The objective of local associations and administrations is to form networks, to pool the problems and the solutions facing an attack which, by this point, is palpable. A recent conference held in Orvieto constituted the first important opportunity for comparing the positions of representatives from different regions. New events are being planned to reinforce the group which means to take shape as a National Network. The Montefiascone ordinance represents, from this perspective, an important precedent which not only signals a significant statement in legal proceedings, but that also confirms the importance of the work done by citizen organisations which oppose the careless exploitation of their land. The flood of hazelnut groves goes on flowing across regions, provinces and municipalities, but the demand for a new production model – one respectful of landscapes, soils, water, biodiversity and that does not base itself on the extraction of primary resources but rather on valorising the local supply-chain – is rising ever stronger and clearer, whether coming from the areas in which the monocultures have already been planted, or from those which watch the advance of the grove wave with bated breath.

Intensive hazelnut monocultures in Fabbrica di Roma (Viterbo). Photography by Manlio Masucci.

A pioneering ordinance: communities working with law enforcement agencies to comply with regulations

The ordinance no. 13 of 22-05-2019, “Measures for stewardship of the environment – regulations on the use of plant-protection products and provisions on intensive hazelnut groves – basin area of Lake Bolsena,” issued by the mayor of Montefiascone, Massimo Paolini, constitutes a model for administrations that want to protect their territory. It is essentially the scrupulous application of existent laws, without affecting constitutional principles such as those relating to the freedom of private initiative. In short, those who wish to cultivate hazelnuts will be able to do so, but will have to comply strictly with all the necessary requirements, under penalty of paying very heavy fines- up to 20 thousand euros- and the withdrawal of authorization.

Among the mandatory requirements, both for existing groves and for those yet to be planted, is the impact assessment (VINCA), a procedure introduced in the ‘Habitat’ Directive. Documentation on water consumption must also be submitted for each hazelnut plot, established or planned, specifying the supply source, irrigation technique, maximum expected annual consumption, and water harvesting permit. Plant-protection treatments, for which there is an obligation to warn the resident population living within a 100 metre radius of the site, are completely forbidden during the flowering period of entomophilous (insect-pollinated) and zoophilous (animal-pollinated) plants as well as during the pre-harvest phases. The use of all plant- protection products containing the active substance glyphosate is prohibited.

A very interesting aspect of the ordinance concerns controls. The community is also called on to do its part in stewardship of the land. “Supervision of the observance of this ordinance and the verification of relevant violations,” the ordinance states, “are entrusted to the staff of the Carabinieri Forestry Corps, the Local Police officers and all other institutional control functions, also with the help of national and local associations for environmental protection in order to involve the whole community actively in precautionary measures and to promote an agroecological transformation of the land.”

The measure is an explicit response to the agreement signed between ‘the Lazio Region and the Ferrero corporation, to promote and subsidize intensive hazelnut groves with Rural Development Plan funds, instead of other methods considered more eco-sustainable for the protection of the lake,” and aims to limit the spread of, ‘a monoculture that famously impoverishes the soil using chemicals harmful to humans and the environment.”

The ordinance reviews the most important reference laws such as Legislative Decree 152/2006 (Environmental Code) which provides for and imposes, ‘the stewardship of the environment and natural ecosystems and cultural heritage,” recalling the precautionary and ‘polluter pays’ principles contained in the European Union’s founding Treaty.

All existing regulations and the general principles of ‘integrated crop protection’ are also applied throughout the municipality, principles that allow a minimal use of chemicals, through the application of the ‘Regulations of the Plant Protection Service of the Lazio Region.” This stipulates the use of balanced cultivation, fertilization and irrigation techniques and the prevention and/or treatment of harmful organisms through monitoring, identification and ‘guided control.” Such techniques are to be based on agronomic bulletins issued by specialised professionals and the use of organic methods, such as buffer crops and attractive traps, physical, mechanical, agronomic and other means.

(Contaminated) water: a common good

Much has been written and debated over the past few years on the effects of pesticides on soils, on aquifers and finally on human health, through independent scientific studies which have at long last questioned the evidence which producers have been sending to standards agencies in order to receive approval for going on the market. The situation in the Viterbese region does not seem different from that of many other regions in the world where the use of pesticides has not been adequately regulated and controlled.ISPRAand ISDE reports show how 63,322 tonnes of pesticides were used in Italy in 2015: most notably in Lazio, where almost 500 tonnes were used in 2016. Statistics which do not even account for those who spray illegally, the professor went on to describe. This is anything but a marginal practice, as shown by Europol’s recent confiscation of 16.9 tonnes of illegal pesticides, worth 300 thousand euros, and found in a storeroom near Vetralla.

Many studies link the use of pesticides to illnesses. According to the 2019 report Cancer in the Viterbo province, 10,098 new cancer cases were diagnosed within the area’s 320,000 thousand residents from 2010-2014. This means that one in every three men and one in every four women in the region will face a diagnosis of a malignant tumour in their life. “There are also reliable scientific studies which link melanoma to exposure to pesticides. When chemical substances are used as herbicides and fertilisers, there is always a lot to be worried about,” Doctor Antonella Litta, from the International Society of Doctors for the Environment (ISDE), confirms. “Exposure to such substances actually correlates with a statistically significant increase in the risk for many illnesses, such as: neoplastic diseases; diabetes; respiratory illnesses; neurodegenerative disorders, Parkinson’s disorder particularly, Alzheimer’s disease, motor neurone disease; cardiovascular problems; disturbances to reproductive functions; metabolic and hormonal disfunctions, the type affecting the thyroids. The risk of blood cancers is especially high. Vulnerability to neoplastic diseases increases for the young children of farmers or those exposed to pesticides, too, especially lymphoma, leukemia and brain tumours,” Litta continues. “Uterine exposure seems particularly high-risk: the chance of developing childhood leukaemia through foetal exposure has transpired to be double than expected for exposure during pregnancy, and this is the same for pesticides certified as suitable for domestic use.”

“So we really need a rapid shift away from intensive and chemical agriculture in favour of a healthier, more natural, ecological, respectful agriculture. That is an agriculture which respects the health and structure of soils, of water and of biodiversity,” Litta goes on to add. “And this demand is in the light of stories as dramatic as they are emblematic about numerous lake basins, in Italy and in the world, including Lake Vico. Its ecosystem is heavily compromised, and so, as a result, is the quality of the water captured and distributed for human use. This is also and chiefly due to decades of intensive hazelnut cultivation in its basin.”

The issue of water resources is one keenly felt in the region where many municipalities have had problems with their potable water supply. As part of a recent conference on the subject hosted by the ‘Biodistretto della Via Amerina e delle Forre’, Professor Giuseppe Nascetti from Unitus underlined how the serious processes of eutrophication (excess of nutrient substances) and anoxia (absence of oxygen), linked to excessive use of fertilisers and pesticides released into the water, are putting Lake Vico at serious risk. ‘Lake Vico is dying,” Nascetti declared. “We have studies from Tuscia University which prove it. We need to curb the urbanisation of our coasts, the use of pesticides and herbicides and the accumulation of red algae, which produces a carcinogenic microcystin. The lake has suffered from the agricultural by-products of hazelnut cultivation and from the enormous use of nitrogenous fertilisers, which have then, as the result of rainfall, spilled into the lake basin.” A situation which has finally made it onto the Environment Minister’s radar, who, following a complaint from ISDE, has sent communications to the regional and provincial offices, to the Regional Agency for Environmental Protection (ARPA) and to the lakeside municipalities of Ronciglione and Caprarola, requesting explanations regarding “the inadequacy of water treatment systems and the presence of substances in potable water which compromise its use as such”. Among ISDE’s requests is, “the rapid roll-out of a drastic reduction, leading to complete abolition, of the use of chemical pesticides in the whole Lake Vico valley with a reconversion of all the current forms of agricultural cultivation present therein to organic methods”.

Update

In September 2020, ISDE’s (International Society of Doctors for the Environment) Viterbo branch received a note from the European Commission’s General Directoratefor Environment, Quality of Life & Water Quality,, regarding the Lake Vico situation, and the quality and safety of the water captured from the lake and distributed in aqueducts in Caprarola and Ronciglione. The note ENV.C.1./HC/AT (2020) 4192057, dated September 11, 2020, states among other things that: “…The Commission is aware of the issues you raised and the potential violation of EU law in relation to the quality of drinking water. An infringement procedure has been initiated to ensure compliance with EU law (procedure 2014/2125) and an assessment of the Italian authorities’ response to the reasoned opinion sent to them on 25 January 2019 is currently underway…”.

The original article was first published in Italian in Terra Nuova magazine, July – August 2020

Translation kindly provided by Kiri Ley. Revision by the Navdanya International Team