Read the report: The Corporate Push for Synthetic Foods: False solutions that endanger our health and damage the planet

Foreword by Dr Vandana Shiva: Artificial Food is Detrimental to Ecological Transition

Download Report pdf

An Impossible Menu: Fake Food Is Taking Over Our Tables

A plate of fortified Golden Rice as the first course, a second course of Impossible Burger, and a side dish of synthetic mozzarella with vegetables grown from genetically modified seeds. Of course, selling such a menu doesn’t really seem easy. However, if it were made clear that such a menu is necessary to protect the environment and that it is also beneficial to our health, then perhaps more people would be willing to indulge. Perhaps there would even be more governments willing to fund private research in this artificial nutrition. There is no doubt that a menu conceived in a laboratory, yet at the same time ecological, represents a captivating narrative. But is this a realistic representation, or are we faced with yet another greenwashing operation to hide the usual interests behind a fluorescent green veneer?

A plate of fortified Golden Rice as the first course, a second course of Impossible Burger, and a side dish of synthetic mozzarella with vegetables grown from genetically modified seeds. Of course, selling such a menu doesn’t really seem easy. However, if it were made clear that such a menu is necessary to protect the environment and that it is also beneficial to our health, then perhaps more people would be willing to indulge. Perhaps there would even be more governments willing to fund private research in this artificial nutrition. There is no doubt that a menu conceived in a laboratory, yet at the same time ecological, represents a captivating narrative. But is this a realistic representation, or are we faced with yet another greenwashing operation to hide the usual interests behind a fluorescent green veneer?

One thing can be said with certainty: the development of the artificial food industry as the best response to environmental challenges is a biased one. The global food industry is in fact trying to reshape its range of products to appeal to an increasingly green consumer base, and it is aware of the fact that many of these consumers are not well-informed about the causes of the current environmental disasters. Disasters that can be largely blamed on the same circle of businessmen, who today finance the development of the biotech industry. Far from wanting to admit its mistakes and contribute to a process of regeneration, it seems that Big Food has found a way to impose yet another set of technological solutions to a series of problems triggered by the very model of industrial agribusiness on which it is based. This represents a billion-dollar business operation.

But even assuming that we have already reached the point where we have no other option than to rely on artificial food, and for this we will forced to pay the multinationals a lot of money, another objection remains unresolved: many of the foods synthesised in laboratories are based on raw materials derived from an industrial agricultural process dependent on intensive monocultures, often derived from GMO seeds and with a high chemical input. In other words, the questionably laudable attempt to save the planet from the negative impact of animal farming rests on the same production system that is destroying wildlife, polluting water and soil, and warming the planet. A vicious cycle that would seem to make little sense if one did not consider the actors behind such proposals. And yet, despite the many contradictions, synthetic food appears to be a surmountable challenge for the industry that has decided to heavily invest in this sector. It is therefore no coincidence that artificial food was high on the agenda at the recent UN Food Systems Summit in New York.

An ecological choice?

Let’s start with the most important question. Is artificial food a real solution to climate change and environmental degradation in general? Certainly, producing food in a laboratory does not involve the direct large-scale exploitation of natural resources such as water and soil. Yet many studies are questioning the alleged sustainability of this industry, which now comprises a constellation of start-ups capable of proposing increasingly ingenious technological solutions. Many companies are investing in cellular meat, also known as cultured meat, made from real animal cells. This same technology is also aiming to revolutionise the dairy sector with so-called cultured milk.

The Canadian company Better Milk, for instance, is investing heavily in the production of cow’s milk using bovine mammary cells. There are now also start-ups who have already thought of applying the same logic to humans. TurtleTree Labs, a start-up based in Singapore and the US, is poised to launch human lactoferrin into the market, as the first commercial cellular product for newborns. US-based Biomilq has also announced that it is ready to market the first synthetic baby milk cultured from human cells. Is this product comparable to breast milk? The company doesn’t claim their product is identical to breast milk, but “it will be free from the environmental toxins, food allergens, and prescription medications that are often detected in breast milk”, because “it is produced outside the body in a controlled, sterile environment free Indeed, this is a well-founded argument, as the latest studies on natural breast milk show. A recent American intercollegiate study found the presence of PFAS in 100% of the breast milk analysed: all 50 samples examined showed the presence of the dangerous chemical substances at levels up to 2,000 times higher than those considered safe in drinking water. Yet, in spite of this, the feeling remains that the industrial apparatus systematically aims to invest in technological solutions in order to profit from the problems it has itself created. This is a perverse logic that allows for the ceaseless pollution of the environment in order to sell artificial solutions.

The Canadian company Better Milk, for instance, is investing heavily in the production of cow’s milk using bovine mammary cells. There are now also start-ups who have already thought of applying the same logic to humans. TurtleTree Labs, a start-up based in Singapore and the US, is poised to launch human lactoferrin into the market, as the first commercial cellular product for newborns. US-based Biomilq has also announced that it is ready to market the first synthetic baby milk cultured from human cells. Is this product comparable to breast milk? The company doesn’t claim their product is identical to breast milk, but “it will be free from the environmental toxins, food allergens, and prescription medications that are often detected in breast milk”, because “it is produced outside the body in a controlled, sterile environment free Indeed, this is a well-founded argument, as the latest studies on natural breast milk show. A recent American intercollegiate study found the presence of PFAS in 100% of the breast milk analysed: all 50 samples examined showed the presence of the dangerous chemical substances at levels up to 2,000 times higher than those considered safe in drinking water. Yet, in spite of this, the feeling remains that the industrial apparatus systematically aims to invest in technological solutions in order to profit from the problems it has itself created. This is a perverse logic that allows for the ceaseless pollution of the environment in order to sell artificial solutions.

Similarly, artificial ‘plant-based’ foods are also based on technical innovations such as synthetic biology, which involves reconfiguring an organism’s DNA to create something completely new, that cannot be found in nature. Companies such as Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods use a DNA coding sequence derived from soybeans or peas to create a product that looks and tastes like real meat. The famous Impossible Burger is made almost entirely from common crops: wheat, maize, soya, coconut and potato. But one key ingredient, heme, the molecule that gives meat its flavour, is not so easy to obtain from natural sources, and this is why it’s synthesised in the lab.

As Pat Brown, founder and CEO of Impossible Foods, declares: “We use genetically engineered yeast [obtained from soy DNA] to produce heme, the “magic” molecule that makes meat taste like meat — and makes the Impossible Burger the only plant-based product to deliver the delicious explosion of flavour and aroma that meat-eating consumers crave.”

Artificial meat is also made up of protein and fat from peas, potatoes, soya, and maize grown in monocultures based on the same heavy processing methods, chemical inputs and GMOs that are compromising global biodiversity, destroying wildlife, altering soils and polluting groundwater sources. Yet, the first point in the marketing campaigns of synthetic food companies remains invariably that of reduced environmental impact. This assumption is difficult to prove, considering that plant-based synthetic foods are based on the exact same system as industrial agriculture. It is therefore no surprise that a recent study by the Health Research Institute Laboratories found levels of glyphosate (and its metabolite Ampa) in the Impossible Burger to be 11.3 ppb. This is more than enough to have a negative impact on our intestinal microbiota and therefore on our immune system. Not to mention the “probable” carcinogenicity of glyphosate declared by the IARC and its now proven ability to act as an endocrine disruptor.

The sustainability of the biotech production system compared to the traditional one has been questioned by numerous studies also from the point of view of GHG emissions linked to climate change. According to recent research, carbon dioxide emissions resulting from the industrial processing of synthetic meat may persist in the atmosphere for hundreds of years, unlike methane produced by traditional intensive livestock farming, which dissolves in the atmosphere after about ten years. As a matter of fact, a large amount of energy is required for the production process, involving several energy-intensive steps, including the operation of the bioreactors, temperature controls, aeration and mixing processes. Given these indicators, the food tech industry is not in a position to boast about the superior ecological performance of fake foods as opposed to that of traditional production systems. Only a total de-carbonisation of energy systems could improve this indicator, therefore, synthetic food does not seem to have a legitimate place in the category of “eco-friendly” food, but rather in the category of ultra-processed food, due to the high-impact transformation process required.

In contrast with traditional plant-based foods these new meat alternatives should be considered ultra processed foods, which nutritionists generally recommend avoiding due to their harmful health effects. A recent study analyses these new synthetic foods from a nutritional point of view, looking at each individual ingredient. Ultra processed foods often contain high levels of sodium and fats in order to be appealing to the palate, and synthetic meat is no exception, since it exceeds the sodium content of natural meat. The ingredients that make up cultured meat are ultra-refined and, like other ultra processed foods, need to be generally supplemented with nutrients and fortifiers. Many of the nutrients found in natural meat, such as iron, zinc and Vitamin B-12, are added as separate ingredients in synthetic meat. However, these nutrients cannot be absorbed as effectively from fortified foods, as they can be from whole foods such as meat, nuts and seeds.

As a consequence our bodies may also obtain less health benefits from them. The researchers thus conclude that a healthy and environmentally friendly diet does not require new technologies and should not include more industrial products that have been heavily processed. Instead, it should be based on organic and regenerative agriculture which offers healthier products with richer nutrients.

Big food: artificial food, natural profit

In light of the above, we cannot claim that artificial food is good for the environment and the health of consumers. What can be said, however, is that it is undoubtedly lining investors’ pockets. Biotech companies and agribusiness giants are building up to invade one of the most promising markets of the near future: that of “green” consumption. The result is a whole range of artificial foods such as meat, eggs, cheese and dairy products synthesised in laboratories.

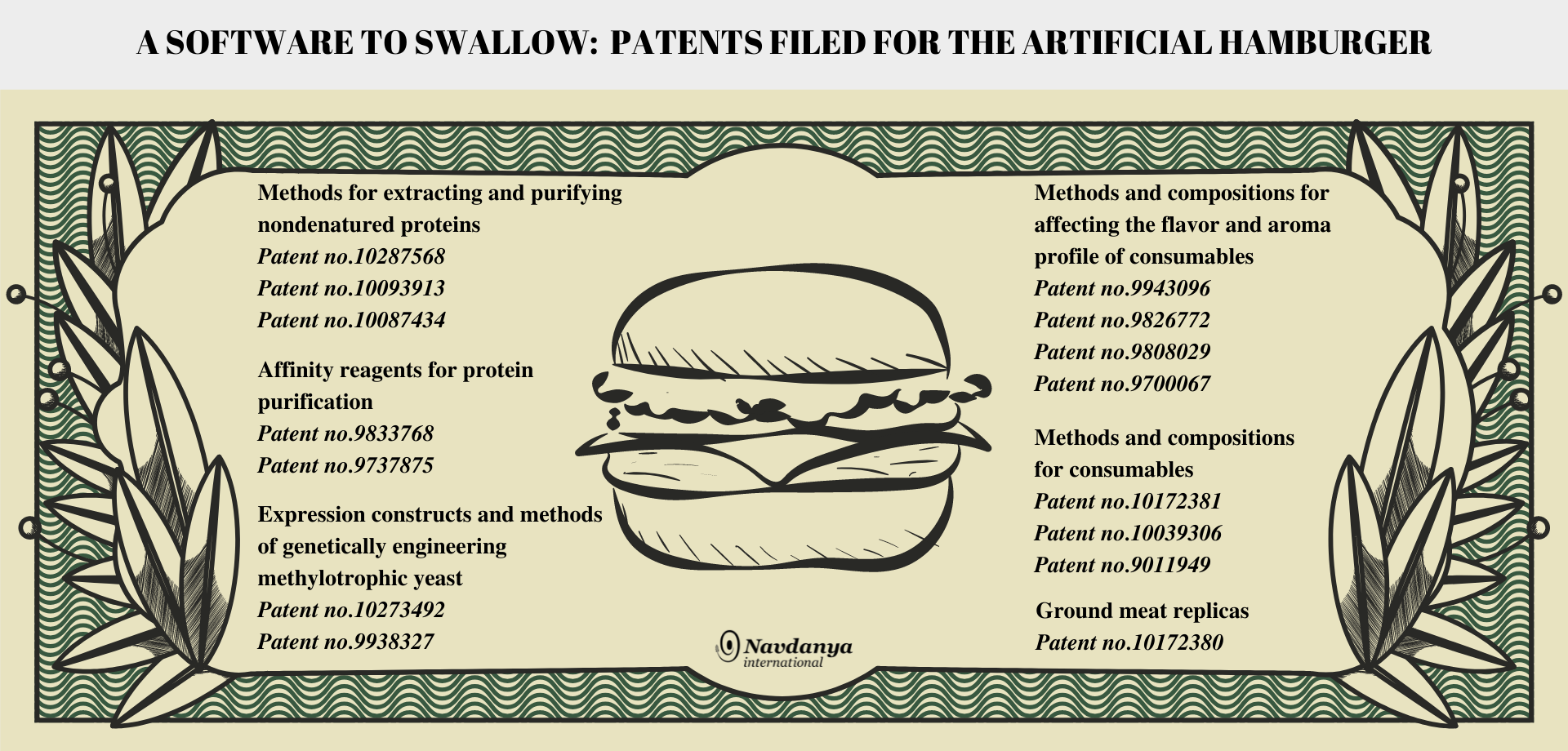

The system is always the same. Especially in terms of patents. For the Impossible Burger alone, at least 14 patents have been filed and hundreds more are waiting to be approved for other synthetic edible products and ingredients. This is an era-defining change of perspective. Firstly, due to the logic of patents, animals and plant products continue to be treated as disposable items that can be simply replaced by more efficient technologies such as laboratory products. Humans’ profound relationship with nature is completely ignored. It is again the CEO of Impossible Foods who explains this relationship well, for those who have not yet understood it: “Animals,” says Pat Brown, “have just been the technology we have used up until now to produce meat…What consumers value about meat has nothing to do with how it’s made. They just live with the fact that it’s made from animals.”

Secondly, because we continue to lose control over the origin and production of our food, we are gradually giving up our food sovereignty. Artificial food does not present itself as a clear alternative for our diet but, by disguising itself as a form of traditional food, it tries to sneak its way onto our tables. It is a full-fledged counterfeiting operation that aims to gain control over our diet by making food evermore dependent on the multinational companies that produce and patent it. However, continuing to hand over control of our food to a few companies can have detrimental impacts on local food systems by eroding people’s food sovereignty. According to biotech companies, nature and its living organisms are nothing more than an exhausted, obsolete technology: “If there’s one thing that we know,” the Impossible Foods CEO argues, “it’s that when an ancient, unimprovable technology counters a better technology, that is continuously improvable, it’s just a matter of time before the game is over.”

Pat Brown, on the other hand, also seems on his game “when he says that his investors “clearly see ‘a $3 trillion opportunity’ emerging on the horizon. The numbers prove him right. The synthetic biology industry is booming. It has reached a value of $12 billion in the last decade and is expected to double by 2025, to reach $85 billion in 2030. This exponential growth is confirmed by the latest Synbiobeta figures: the first quarter of 2021 saw record investments in start-ups of $4.7 billion and $4.2 billion in the second quarter. In the last twenty years, the number of companies specialising in this field has risen from less than 100 in 2000 to more than 600 in 2019. Beyond Meat has been one of the “hottest” stocks in 2019. The plant-based meat company’s shares grew a whooping 859% during its first three months.

It is no coincidence that, alongside industrial giants such as Cargill and Tyson Foods, even the biggest ‘environmental’ philanthropists are investing in this sector. Bill Gates, for example, has invested in Impossible Foods, Beyond Meat, Memphis Meats (now Upside Foods), Motif and Hampton Creek Foods and Biomilq. A path followed by Richard Branson and Jeff Bezos, founders of Virgin and Amazon respectively. There are even some investments for products made in Italy.

A German start-up company, Formo, has just received record funding from its shareholders of $50 million to develop large-scale production of ricotta and mozzarella in the laboratory. The funding represents a record for a European foodtech start-up and sends a clear signal to investors and markets around the world.

Fortified and ultra-processed food

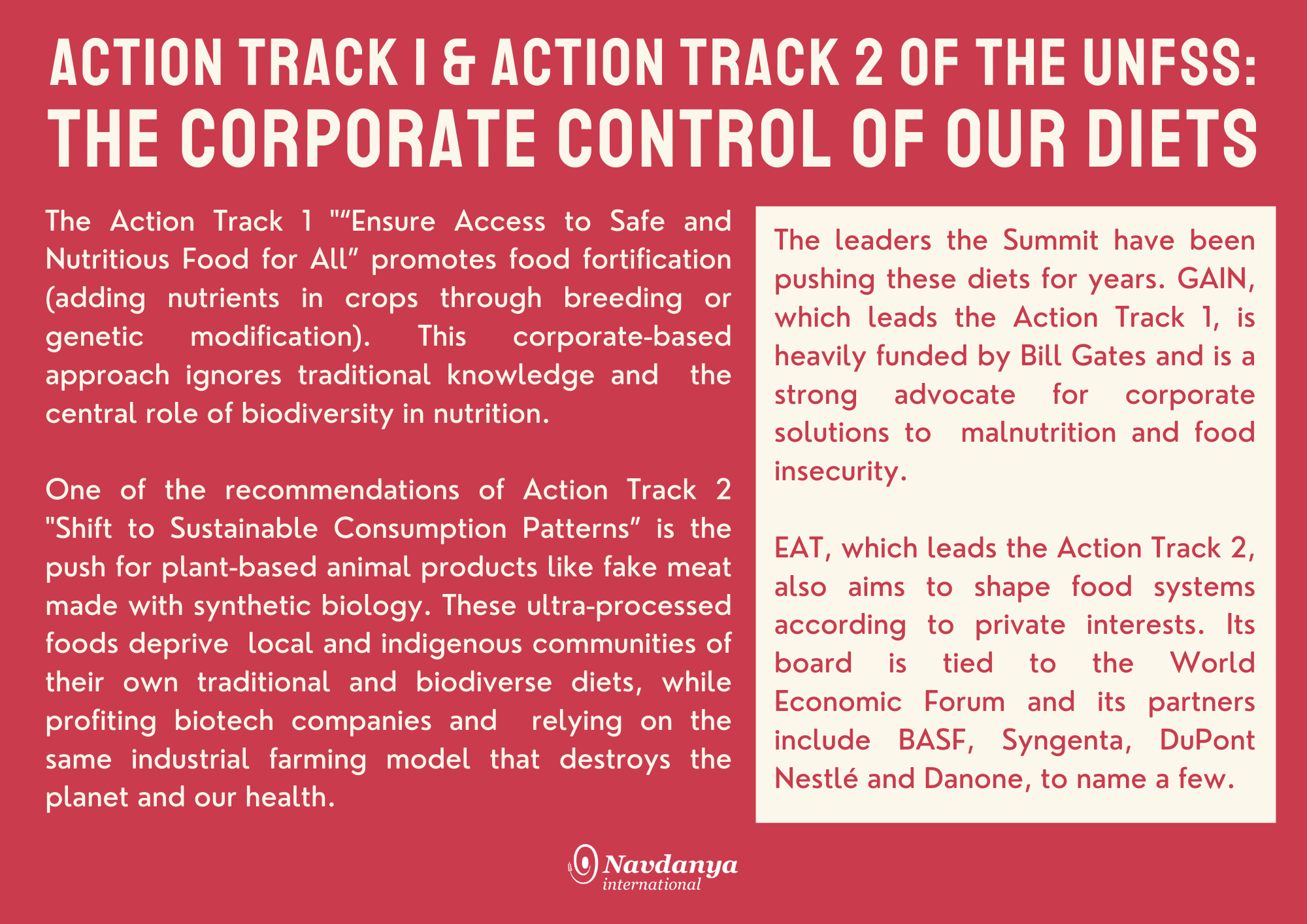

The recent Food Systems Summit in New York, held last September amid protests from international environmental associations, is perhaps the place and time where the intentions of the food multinationals found their best expression. In pages and pages of documents, mentions of organic or agroecology can be counted on one hand and, even when they are mentioned, they seem to play a mere sideline function. The development model must remain the same, namely that of the failed but profitable Green Revolution. The actors involved, i.e. the big investors and the agribusiness multinationals, must also remain the same in order to continue to profit from the new technological investments. What they believe needs to be radically changed is, quite simply, the narrative. This is the only truly green element to be found in the action plans of the masters of food. Yet, it cannot be said that we had not been warned. After all, Action Track 1 and 2 of the Summit lay out the global strategy very thoroughly.

Action Track 1, ‘Ensure access to safe and nutritious food for all’, promotes large-scale food fortification as a solution to malnutrition. Food fortification is the process of supplementing food with additional nutrients. This process may also involve the use of biotechnology and genetic modification. It is an approach often recommended, and put into practice, in developing countries where nutritional deficiencies are found. Expanding and enriching the diet, to ensure access to healthy food for the population, could solve many problems. However, multinational companies think it is cheaper to market only one fortified food.

A classic example is Golden Rice, a rice genetically modified to contain levels of beta-carotene that can remedy vitamin A deficiencies in the population. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has so far given $28 million to fund Golden Rice. The project is in direct collaboration with the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (Gain, founded in 2001 by Bill Gates). Gain, leader of Action Track 1, was among the first organisations to use the public-private partnership model. Since then, it has continued to support biofortification projects to combat malnutrition and food insecurity. Gain also shares many of the same donors as AGRA (Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa), such as the Rockefeller Foundation, BSF or Unilever, and received no less than $251 million from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation between 2002 and 2014.

The approach based on fortifying one single food rather than increasing the diversity and quality of foods available has, according to many observers, undermined the ability of communities to strengthen local food systems that are based on cultural and traditional knowledge, thereby destroying their food sovereignty. Policies pushing for biofortification, like other technological solutions, are accused of inducing dependence on a handful of staple crops or single added ingredients, thus ignoring the central role of biodiversity in nutrition. Simply adding one nutrient does not seem to be able to solve the problem of malnutrition, but it does seem to produce excellent profit margins for the agribusiness multinationals.

One of the countries most involved in food fortification programmes is Bangladesh. A recent analysis by activist Farida Akhter captures the contradictions of an approach that continues to develop along the corroded tracks of the green revolution: “Monoculture rice crops, using almost 80 percent of the land, are resulting in a deficiency in the production of other essential food crops needed for nutritional balance. Poor dietary diversity, with 70 percent of the diet comprising cereals and inadequate protein and micronutrient intake is blamed but it is not mentioned how the monoculture production and use of pesticides affect the availability and quality of food and nutrition. Instead of transforming the chemical-based agriculture, new techn-fixing of few food items, edible oil fortified with vitamin A, rice fortified with zinc, salt fortified with iodine are offered as solutions to malnutrition. These are not the only foods that people eat. An agroecological and biodiversity-based approach to farming for food production would solve most of the problem”.

Many other examples of public-private partnerships to genetically modify (or biofortify) crops exist. For example, sorghum through the Africa Biofortified Sorghum Project, and cassava by the BioCassava Plus project in partnership with the National Root Crops Research Institute in Nigeria. Both projects aim to improve nutrition security and correct vitamin deficiencies in Africa by fortifying staple crops and supplementing them with beta carotene, which the body then converts to vitamin A, Iron and protein. The list also includes the controversial GMO banana, created by Dr. James Dale at Queensland University of Technology, which has received over 15 million in funding from the Gates Foundation and is now being pushed in India and Uganda. While the imposition of this iron-enriched GM crop claims to save women’s lives by remedying iron deficiencies in anemic women and preventing death during childbirth, it may instead contribute to the erosion of biodiversity in India, which has always had a high diversity of bananas, as well as other iron rich foods.

Moreover, GMOs are also starting to be falsely equated to biofortification in order to greenwash them further and allow them to sneak their way into our foods. This became apparent at a Codex Alimentarius Meeting held in Germany where despite opposition from a majority of the countries present, there was a clear push for including GMOs in the biofortification definition. Needless to say, such a controversial decision would promote market deception and illustrates a lack of transparency in establishing food standards and guidelines. If the pro-GMO forces are able to continue hiding their genetically modified foods within the definition of biofortification, consumers will be deceived on a worldwide scale and deliberately left confused about whether they are buying organic products or something else entirely.

Action Track 2 of the Summit, “Shifting to Sustainable and Healthy Consumption Patterns”, is also based on solutions whose sustainability is highly questionable. The action plan is essentially based on the promotion of artificial and ultra-processed plant-based foods with the aim of achieving “protein diversification”. This approach leaves many doubts because, just as in the case of food fortification, simply adding isolated proteins, vitamins and minerals to diets does not seem to have the same health benefits as fresh, whole foods. The excessive processing of products has in many cases led to strong controversy about the many chemical substances used, so that many of these foods fall firmly into the category of ‘junk food’.

Interestingly, leading Action Track 2 of the Summit is EAT, an organisation linked to the World Economic Forum, with partners such as Nestlé and Danone, both leaders in the production of ultra-processed foods. The recommendations of the action plan come directly from the EAT-Lancet report “Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems”. This is a highly controversial report because, while on the one hand it calls for sustainability and the transformation of food systems through the promotion of ‘healthy diets’, on the other hand it glosses over the direct role of industrial and chemical agriculture in creating unsustainable and unhealthy food systems. The report never comes close to considering that the adoption of healthy diets may depend on a departure from the industrial agriculture paradigm and the adoption of agroecological practices. Instead, it promotes the notion of ‘sustainable intensification’ of current food systems with a shift in the global consumption axis towards ‘plant-based’ alternatives. A solution that, once again, threatens to replace biodiverse and local diets with ultra-processed synthetic foods produced with patented technologies that are highly profitable only and exclusively for the agribusiness multinationals.

EAT has a partnership through FrESH with the junk food industry, and Big Ag such as Bayer, BASF, Cargill, Pepsico amongst others.

Which future for our diets and the planet?

It is clear that it would be difficult to sit down in a restaurant today and confidently order an entire menu of artificial food. Yet, in the near future, this choice might not seem so bold. In fact, it might even sound like a responsible one. In an even more distant future, this may no longer be a choice, but instead the only option for not getting up from the table hungry. In this future, which is perhaps closer than we think, there may be fewer choices than we have today. If agroecology and organic production are not adequately supported, that future, which seems dystopian to us today, may actually come true due to a lack of alternatives.

Some might object: but aren’t the EU’s Farm to Fork and Biodiversity strategies asking us, among other things, to expand the area under organic production by 25% and cut pesticide use by 50% by 2030? The answer lies in the implementation of these strategies, which should primarily take place through a reform of the CAP, the EU’s agricultural policy which, when allocating resources, prefers to subsidise large-scale conventional producers. Finally, it should not be forgotten that the Farm to Fork strategy itself nods to the new technologies of genetic manipulation, which includes the new generation of GMOs. This is yet another gift to the big multinationals in the sector who, through their pervasive and costly lobbying campaigns, always manage to land on their feet. All this considering that the EU’s policies remain, by far, the most progressive globally.

If this is the larger scenario in global politics, what happens at the individual level? Consumer choices have a major impact on markets, as demonstrated by the growth of organic worldwide. According to IFOAM, 2020 showed the highest growth of the global market for organic products, growing to 120 billion euros. Consumers instinctively mistrust synthetic food and this is perhaps why there is a need to accompany these products with an ecological narrative. But this narrative struggles to stand on its own. While vegetarian and vegan diets have the potential to have a positive impact on the environment, artificial meat, egg and cheese substitutes may not. On the contrary, there is much to suggest that the biotech industry is not as sustainable as it claims to be, regardless of their promising and vast greenwashing campaigns aimed to capture a growing number of consumers who genuinely want to make greener food choices. This is the same group of consumers who, if not misled by the industry’s greenwashed narrative, would most likely opt for an organic diet, thus favouring market growth and therefore the overall food supply. From this point of view, large investments in the biotech and synthetic food industries could further delay those regenerative and truly sustainable processes that are trying to emerge, regardless of the great difficulty, at a local level all over the world.

Source: An Impossible Menu: Fake Food is Taking Over Our Tables, Manlio Masucci, Terra Nuova magazine, February 2022